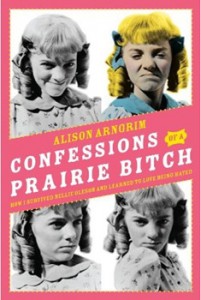

I read “Confessions of A Prairie Bitch“ in one sitting, because it is that kind of book. “Prairie Life”, which I read earlier this year, is that kind of book, too. If you were a girl growing up in the 1970’s like I was, if you were a card carrying nerd like I was, if you were very limited in what you were allowed to watch on tv like I was, and if you read everything not nailed down so that you knew every line of every book in the Little House book series like I did, then you probably watched the NBC TV series, Little House on the Prairie. And if you watched Little House on the Prairie then it is likely that you were anywhere from reasonably to perversely obsessed with the girls on the prairie. And the only two girls that mattered – in all of Walnut Grove – were Laura Ingalls and Nellie Olseon.

Alison Arngrim was the lucky duck cast to play Nellie, the parodic “spoilt rich girl” we all envied and feared. You know, the thoroughly fictional character type with petticoats and golden sausage ringlets, that has never actually existed in reality. For those of us familiar with the books, that first Garth Williams illustration of Nellie was etched in our brains forever: Fancy, fancy Nellie, petticoated and sausage curled, snatching her costly doll away from poor, bedraggled Laura’s filthy prairie finger.

Sadistic, stuck-up Nellie is the perfect foil for Laura – whose heart is golden but hair is brown – whether inappropriately boasting about her home’s fineries in a school essay, taunting the poor, the crippled and the stuttering, whipping the crap out of Laura’s pony, or committing the monstrous act of faking paralysis – psychopathically enduring Doc Baker’s needles in her toes without batting an eyelash. It is after Nellie’s great deceit is exposed that she transforms – via a tour de force performance where she batters her dollhouse with a hairbrush shrieking “I hate you, Laura Ingalls!” – from a flouncing brat into a truly deranged child villainess, finding new ways to torture, humiliate and blackmail Laura every week. Nellie worked in large part because of the comedic prowess of the actress. With another kid, she may have been just a sadistic brat. It’s this breezy jocularity in the face of trauma, and her abilities as a buoyant and natural storyteller that makes Alison’s story a one sitting page turner rather than a big downer.

Growing up in various Los Angeles neighborhoods (but never East of Fairfax), Alison Arngrin was my polar opposite and object of unobtainable envy. She was California and in Philadelphia, she seemed as exotic and mysterious as a Saudi Arabian harem girl – sunny, golden, with long straight blond hair. She was also endowed with a sparkly, sweet and salty personality. She was the sunshiney innocent, the perfect daughter and sister, and the trusty, wisecracking tomboy best friend.

The real story that emerges from her cheeky memoir has little to do with Nellie, or even with being a child star. It is her life that is the story. It is hard to imagine a life – even by Hollwood standards – more colorful or more horrific. Her childhood was full of contradictions: glamorous but frightening, privileged but criminally neglectful, public but deeply secreted. The Arngrim parents were wildly quixotic free spirits. Her father – a self described “entrepreneur” – had a wide variety of jobs, “anything that didn’t require a high school diploma.” It was a poorly kept secret that he was gay, particularly to his whip smart 6 year old daughter. Her mother was Norma MacMillan, an enormously gifted and prolific voiceover actress who voiced a stable of iconic cartoon characters (Sweet Polly Purebred, Casper, Gumby). The Arngrims supported their children’s creativity but were barely able to keep food on the table or a roof over their heads. Being attractive and charming in Hollywood is often cover enough for parental failings and neglect. They lived in a series of glam addresses like the Chateau Marmont and the dreamy Hayworth Tower, but were monumentally ignorant of anything going on under those roofs. This was the 1970’s and “the more you know”, the more that era resembles the simulated wild west of the Simi Valley prairie set and less a modern, civilized society.

Nellie Oleson, stripped of her petticoats and wigs, was a brave little tomboy in bicentennial shorts and a Slurpee stained mouth. The sick twist to the story is that she was being raped by her brother, the evil Stefan Arngrim, who is some kind of modern monster that wouldn’t be a believable villain in a Ruth Rendell novel: washed up child star turned washed up teen heart throb (he was in Tiger Beat), junkie psychopath. Apparently, whatever small successes he had as a child earned him Lord of the Manor rights, abusing his kid sister, feeding her drugs, and using the family den as an orgy parlor and shooting gallery. Alison did not have the agency to stand up to her “brother”, or  give voice to her trauma, until she was cast as Nellie Oleson and was given a primal outlet, simply through Nellie’s weekly rages and tantrums. Playing Nellie taught Alison that a little girl can be in control of her own life, be independent and courageous and have an adventurous life. Nellie satisfied Alison’s desire for domination, because as nasty and vicious as the little brat could be, she was a girl with power. Nellie dominated every man in every scene, then turning with a flip of a curl and a flounce of her dress as she walked away. I had Nancy Drew, she had Nellie Oleson. Nellie Oleson saved Alison’s life.

The demonic brother was never held accountable, and actually has a website – a testament to how shitty the 1970’s were. Can you imagine Mrs. Oleson standing by passively while her Nellie was being abused? Even Pa would have protected his daughter’s nemesis with his strap and a shotgun (remember what happened to the vicious teacher who beat the kids with a ruler?), and the townsfolk as back-up. Remember when the greedy land baron tried to enslave the townsfolks and – sick of the blizzards, droughts, economic tailspins, quarantines, fires, Jesse James, rabies, locusts and typhus – all go haywire? Years of suffering and deprivation that had really gotten them nothing and nowhere – plus a supply of illegal explosives – resulted in a ritualized laying of dynamite and the blowing up of every mercantile, grainery, schoolhouse and outhouse. They blew up the entire town. They blew Walnut Grove to bits while the greedy tycoon looked on in horror. The usually maddeningly placid town pastor turned purple and uncharacteristically raged: “Walnut Grove did not die in vain!!” and the townspeople rolled out in their wagons singing “Onward Christian Soldiers.”

Sadly, Alison’s dad was no Pa Ingalls, her mom was no Harriet Oleson and Hollywood, as we know, is no Walnut Grove.

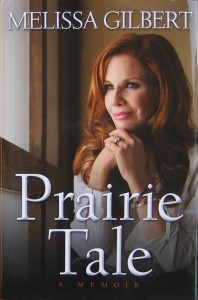

Meanwhile, over in the San Fernando Valley, Alison’s co-star, Melissa Gilbert, was being coddled like a pig-tailed princess in a tower aka five-bedroom home in Encino with pool, guest house and two fridges. In her frank and insightful memoir, Melissa describes how her suffocatingly overprotectve mother – lovely actress Barbara Crane  – scheduled and controlled every minute of her life, never leaving it up to chance that her daughter be a good girl. While Alison was being starved (the poor thing gorged on peas and dinner rolls while shooting the Oleson’s “dinner scenes“), Melissa was being force fed and fussed over. The itty bitty 9 year old found her emancipation on the set, marching around, calling meetings, counseling her co-stars. She was an inspired bit of casting. From the pilot and every episode after that, she gives an open, mature, nuanced performance. She is never cutesy or cloying. She is feisty but empathetic, tough but vulnerable, good but subject to petty jealousies and sibling rivalries. She is always believable and dominates every scene.

“Pa”, aka Michael Landon – in skinny britches and tipsy on moonshine – became a father figure to Melissa after her own Pa – actor Paul Gilbert – passed away. Landon’s family became her surrogate family – a complicated scenario for a sensitive 9 year old, the fallout from which continued into her adulthood. Melissa’s sheltered life dragged into her adolescence with one foot firmly stuck in childhood. Maybe it’s the power of The Valley, but the reality of a child star being successfully shielded from the seedy atrocities of 1970’s Hollywood is kind of a miracle. In one of my favorite anecdotes from the book, Melissa’s mom somehow convinces her 16 year old daughter to purchase – as her first car – a cream colored, Chrysler LeBaron station wagon (Melissa Sue Anderson bought herself a flame-red sports car). She was a Hollywood anomoly, a late bloomer, a self-confessed “repressed, dorky child star”. Her first kiss was to her on-screen beau (the tragically cast “Manly”), and she wasn’t permitted to cut her hair (let’s be honest, this was absolutely a blessing. While other girls are sentenced to perennial dorkdome with their featherings, wings and poufs, Melissa always had a timeless mane of auburn hair).

By the sleazy standards Hollywood set for its teenage actresses at the time, Melissa was in arrested development while her teen rivals embraced that ritual “put out or shut up” age with gusto. One exception was brown haired, preternaturally athetic Kristy McNichol (who kicked Melissa’s ass on the Battle of the Network Stars, but lost in the battle of the hair), who was good in every role and who gallantly never shed her inner tomboy. The other girls, like disco partygirl Tatum O’Neal (topless muse) Linda Blair (reform school girl), Donna Wilkes (teen prostitute), Jodie Foster (teen prostitute) and Brooke Shields (child prostitute), seemed to move effortlessly into that next stage, shedding their inner little girls and taking off their tops. It was reasonable to assume that these chicks had done a lot more than smooching a sexy-as-a-stool prairie dude on a tv sound stage. Gilbert remained girlish, artless, unsophisticated, while quietly churning out artful and sophisticated performances as Deanie, Anne Frank and Helen Keller.

Remember when Laura punched Nellie in her fucking face?

Two little girls, at the same time in history and in the same city, on the same long running tv show, one freckly brown, the other sun washed blonde, playing bitter enemies and leading completely disparate lives, forged a friendship spanning decades, because it’s like that with children – they seek out their similarities rather than let their differences define their relationships. One of these similarities was their mutual hatred of moon faced, ice queen Melissa (“Missy”) Sue Anderson, whose translucent eyes and weirdly detached disposition caused a 9 year old Melissa to insist she was “evil” and she “hated her”. In both Alison and Melissa’s accounts, they manage to affectionately portray unvarnished portrayals of the Little House cast and crew, with the exception of Missy. Read between the lines: she is an unmitigated bitch. One wonders if Michael Landon realized his mistake and turned on Missy, because it seems that he did everything in his fictional TV power to destroy her via her character’s misfortunes. The most traumatizing episode is when Mary goes  blind – even though I had read the book and knew it was coming. Missy herself was abject when first told that Mary – as written in history – was going to go blind, pretty much ruining her character. First came the granny glasses that hid her best feature – those spooky eyes – then Ma gets fed up with her blind moping and sends her packing. Following through on the Missy payback theme, Mary becomes the object of unrelenting melodrama and abuse (miscarriages, evictions, fires) ’til series end. At the dismal blind school, she is married off to an (admittedly handsome – not that she can see him), blind guy. But in an act of supreme cruelty, he gets his sight back, and she does not. How much more do I have to bear, Ma”?? she shrieks. How about a 4-alarm fire at the blind school during which your infant son burns to death?? Long suffering Mrs. Garvey also dies horrifically in the fire, screaming for her life, smashing her bloodied hands through the window panes while clutching Mary’s infant son, seemingly using the baby as a battering ram – as if she is using Mary’s baby to bust out the windows…. Later, Mary sits amongst the smoking ruins of the school, rocking her charred baby’s corpse and psychotically humming Brahm’s Lullaby. Recuperating at Nellie’s later, she snaps, smashing her own hands through windows, then falling into a catatonic state, more glassy eyed than usual. Melissa Sue Anderson rarely worked again.

blind – even though I had read the book and knew it was coming. Missy herself was abject when first told that Mary – as written in history – was going to go blind, pretty much ruining her character. First came the granny glasses that hid her best feature – those spooky eyes – then Ma gets fed up with her blind moping and sends her packing. Following through on the Missy payback theme, Mary becomes the object of unrelenting melodrama and abuse (miscarriages, evictions, fires) ’til series end. At the dismal blind school, she is married off to an (admittedly handsome – not that she can see him), blind guy. But in an act of supreme cruelty, he gets his sight back, and she does not. How much more do I have to bear, Ma”?? she shrieks. How about a 4-alarm fire at the blind school during which your infant son burns to death?? Long suffering Mrs. Garvey also dies horrifically in the fire, screaming for her life, smashing her bloodied hands through the window panes while clutching Mary’s infant son, seemingly using the baby as a battering ram – as if she is using Mary’s baby to bust out the windows…. Later, Mary sits amongst the smoking ruins of the school, rocking her charred baby’s corpse and psychotically humming Brahm’s Lullaby. Recuperating at Nellie’s later, she snaps, smashing her own hands through windows, then falling into a catatonic state, more glassy eyed than usual. Melissa Sue Anderson rarely worked again.

Neither of the little girls on the prairie left the set without absorbing some of that faux figthin’ pioneer spirit. They could have given in and signed up for that special club that exists only for former child stars, the one that gives everlasting life to self pity, parental resentment or actual patricide, regret, industry resentment, massive plastic surgery, latent adolescent self awareness and self loathing. And drugs. Alison avoided this by being precociously self aware and putting herself on the therapist’s couch very early on. She doesn’t have Nellie’s sausage curls (it was a wig!!!!), but the same withering wit she brought to Nellie she brings to everything else. Melissa, as we all know did eventually grow out of her arrested girlhood and into a smoking hot mama who bagged a pre-douchebag Scott Baio and an in-his-prime Rob Lowe. She also ran for (and won) the SAG presidency and stopped a free fall in it’s tracks by getting her ass to AA. I spent an afternoon with her and she could not have been sweeter, funnier or more down to earth. There must have been something about that those fake pioneers, in those fake prairie dresses, in that faux pioneer town on that fake prairie set that was real.

Confessions of a Prairie Bitch

By Alison Arngrim

(It Books, Hardcover, 9780061962141, 320pp.)

Publication Date: June 2010

Prairie Tale, A Memoir

By Melissa Gilbert

(Simon Spotlight Entertainment, Hardcover, 9781416599142, 384pp.)

Publication Date: June 9, 2009