Ah, the English boarding school of fiction! Happy schoolgirls scrambling over undulating green hills and hedgerows to classrooms in former manors or castles. Twins, unruly tomboys, sheltered small town bumpkins, spoilt brats, mysterious foreign exchange girls, sexually ambiguous jocks who go by “Billie”, “Bobby” or “Al”, scatterbrained math geniuses, jolly horse-crazed gals, overly invested language teachers no nonsense lacrosse coaches with super short hair… French lessons and proper sports like lacrosse and cricket, great gymnasiums with ropes and vaulting horses, gymslips and pinafores and tunics with black velvet ties…kitchen raids, secret languages, picnics and pillow fights. For those of us who went to regular school (Quaker school no less), English boarding schools  seemed quintessentially romantic. Sent to countryside edens, away from parents and siblings and into the arms of motherly yet non meddling mistresses – freed from the shackles of real parents, but without the ennui of actual dead parents – and into a cloistered, feminine world with rituals, codes and bells and no-nonsense mistresses to impose order and safety. In boarding school, small incidents have more intensity, and overwrought friendship dramas grow from the passionate and rebellious teenage soul that longs to be accepted everywhere and deep, forever friendships form, verging on the romantic. Of course there is always the snoot, the troublemaker, the strict mistress, but it always sorts itself out, even if it means sometimes “getting your corners knocked off”. Because above all, you are a community. You are recognized for your individuality but you’re part of a herd. You belong.

seemed quintessentially romantic. Sent to countryside edens, away from parents and siblings and into the arms of motherly yet non meddling mistresses – freed from the shackles of real parents, but without the ennui of actual dead parents – and into a cloistered, feminine world with rituals, codes and bells and no-nonsense mistresses to impose order and safety. In boarding school, small incidents have more intensity, and overwrought friendship dramas grow from the passionate and rebellious teenage soul that longs to be accepted everywhere and deep, forever friendships form, verging on the romantic. Of course there is always the snoot, the troublemaker, the strict mistress, but it always sorts itself out, even if it means sometimes “getting your corners knocked off”. Because above all, you are a community. You are recognized for your individuality but you’re part of a herd. You belong.

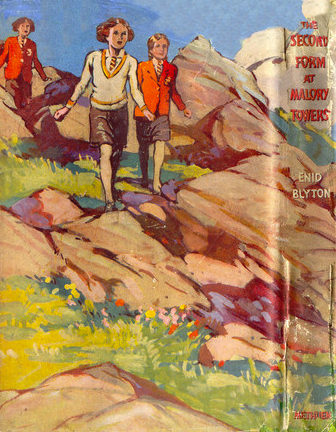

I’ve read the entire canon of boarding school series and am familiar with all those schools. Enid Blyton’s St. Clare’s is the sensible school to where snooty twins Pat and Isobel O’Sullivan are sent kicking and screaming to be “straightened out”. Of course they love St. Clare’s and it does straighten them out. In “The Naugtiest Girl” series, spoilt Elizabeth is sent to the coed and progressive Whyteleafe School, housed in a former country house. Dreamy Malory Towers is located in picturesque Cornwall by the sea, in a stone castle on the cliffs with turrets and a rock ensconced swimming-pool filled with seawater by the tides.

In more serious form:Â The Marcia Blaine School for Girls in “The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie” is the height of sophistication, as is Lucy Snow’s glamourous Belgian pensionnat, Madame Modeste Maria Beck’s School for Girls in “Villette”, set in a medieval city and legendarily haunted by a young nun buried alive for committing an act in breach of her vows. Even Fernanda Grey’s Convent of the Five Wounds in “Frost in May” – for all it”s draconian opressions and cruelty – had it’s medals, parma violets, “exemptions” tied with pink ribbon and schoolmates like aqua eyed beauty Rosario de Palencia, and Leonie De Wesseldorf, the rakish, husky voiced poet in a paquin coat. Even Sara Crewe’s freezing garret at Miss Minchin’s Select Seminary for Young Ladies seemed, well, cozy.

And then there is Hailsham

Hailsham seems like your typically idyllic boarding school – a pretty English Arcadia with ponds, sports fields and winding bucolic paths. It’s where our protagonist Kathy, and her schoolmates Ruth and Tommy, spent their blissful childhoods. Kathy’s descriptions of the rituals and ordeals of student life at Hailsham are familiar: bantering, sniping, teasing, joining and abandoning cliques, teachers reminding them of their “specialness”. But for all it’s generic familiarity, Hailsham is odd. The curriculum is basically art and sports. There is no mention of family or holidays. The teachers and “guardians” behave with subtle strangeness, and seem to regard their students with pity, even fear. And despite the care lavished on them, and the seemingly privileged setting, the Hailsham student’s world is curiously second-hand. Everything they own is crap. Every month “a big white van” brings the flotsam and jetsam of the outside world for their “sales”. “Looking back now”, Kathy reflects, “it’s funny to think we got so worked up, because usually the Sales were a big disappointment. There’d be nothing remotely special and we’d spend our tokens just renewing stuff that was wearing out or broken with more of the same”. Students cared for on the cheap? Â No ponies? I know this is not what boarding school is supposed to be.

The students themselves are at first glance are also familiar. You suspect Kathy may be Miss Brodies’ Sandy Stranger and her best friend Ruth, Rose Stanley. But, unlike the precocious Brodie girls, they seem juvenile, curiously dull. Kathy is minutely observant with carefully blinkered emotion, but her voice is flat and the details she provides are puzzlingly abstract, rarely visual or sensual. Ruth is vaguely moody and bossy, yet jejeune, with imaginary horses to command a secret guard to protect her favorite guardian. In Kathy’s memory: “I was never sure if Ruth had actually invented the secret guard herself,… but there was no doubt she was the leader.” Tommy seems like a lunatic, flying into rages at the football pitch for which he is cruelly ridiculed, until he has a secret meeting with a sympathetic teacher who tells him that the importance his classmates place on their artistic abilities may be misplaced and he is free to “fit in”.

The students themselves are at first glance are also familiar. You suspect Kathy may be Miss Brodies’ Sandy Stranger and her best friend Ruth, Rose Stanley. But, unlike the precocious Brodie girls, they seem juvenile, curiously dull. Kathy is minutely observant with carefully blinkered emotion, but her voice is flat and the details she provides are puzzlingly abstract, rarely visual or sensual. Ruth is vaguely moody and bossy, yet jejeune, with imaginary horses to command a secret guard to protect her favorite guardian. In Kathy’s memory: “I was never sure if Ruth had actually invented the secret guard herself,… but there was no doubt she was the leader.” Tommy seems like a lunatic, flying into rages at the football pitch for which he is cruelly ridiculed, until he has a secret meeting with a sympathetic teacher who tells him that the importance his classmates place on their artistic abilities may be misplaced and he is free to “fit in”.

There are vague, perplexing allusions, and the larger world is a distant, blurred backdrop, but you begin, like the students, to accept the normality of their lives (and I have begun to suspect that there may not be any trouble making twins, no horsey tomboys, no Leonie de Wesseldorf). Not unlike children everywhere, the students fill in the blanks of their cloistered lives and fend off the shared fear of the unknown and the chaos of existence with stories, myths, taboos and fantasies, and by making up their own rules. The spooky legend of the woods is particularly profound, as unquelled legends of the terrible fates of those that dared to wander into the woods. The tale of a girl who is not permitted back after wandering off into the woods elucidates the confines that the woods impose, and their fear of displacement and alienation from Hailsham. They are “fearful of the world around us, and — no matter how much we despised ourselves for it — unable quite to let each other go”.

The style with which Kazuo Ishiguro tells the story defines and defends everything about this novel. It’s so infinitely subtle, touching everything with austere minimalism of description and use of understatement and elision, that you rely on what’s implied as much as what is told. The story is so abstractedly explained and blanketed in the banal, that you able to accept the fantastic elements – those of society’s “advancements”, as well as the limitations of those advancements – and the story is sadder and more plausible for its conceptual short-cutting. Self-consciously in the “late 1990’s”, in an alternate history, in an alternate England, in which science has advanced fifty years earlier than it has in our world. Through 288 pages worth of reading between the lines and having the truth doled out in increments, through counterposing and unravelling its meticulously woven fabric of hints and guesses, insinuating and disconcerting narrative effects, Kathy’s circuitous talking, and the teachers off-kilter behaviour and oblique hinting, were let in on the secret. That what their childish fear of the woods reflects – in a juvenile but fundamentally accurate way – is their fate. The students at Hailsham are human clones, farmed solely for the purpose of organ donation – piecemeal until death – in early adulthood.

The purpose of Hailsham is to prepare it’s students for their future – to instill them with the agencies of self-repression, deference and denial that will keep them dutiful and reliable donors. The gift that Hailsham offers, is the gift of childhood. The Hailsham students grow up in an age that is liberal toward their kind, when society would sanction the Hailsham “experiment”. Born of good intentions, the “experiment” educates and treats their students – who stand no chance of happiness in later life – as special, in a nurturing and sheltered environment. The guardians are nun-like in their devotion to the idea that clones are more than the sum of their bodily parts, that they are creative and artistic in childhood (the student’s best art is secreted out as proof of their humanity to the outside world), deserving a childhood, if not an entire life, that they possess souls. Hailsham was intended to be “a shining beacon, an example of how we might move to a more humane and better way of doing things”, and the guardians are divided as to the logic of protecting the clones from the haunting reality of their adult lives. During their final semester, a distressed guardian overhears the student’s discussing their futures – the poignant and pathetic teenage prattle of optimism, fantasy and banal ambition – and admonishes them:

The purpose of Hailsham is to prepare it’s students for their future – to instill them with the agencies of self-repression, deference and denial that will keep them dutiful and reliable donors. The gift that Hailsham offers, is the gift of childhood. The Hailsham students grow up in an age that is liberal toward their kind, when society would sanction the Hailsham “experiment”. Born of good intentions, the “experiment” educates and treats their students – who stand no chance of happiness in later life – as special, in a nurturing and sheltered environment. The guardians are nun-like in their devotion to the idea that clones are more than the sum of their bodily parts, that they are creative and artistic in childhood (the student’s best art is secreted out as proof of their humanity to the outside world), deserving a childhood, if not an entire life, that they possess souls. Hailsham was intended to be “a shining beacon, an example of how we might move to a more humane and better way of doing things”, and the guardians are divided as to the logic of protecting the clones from the haunting reality of their adult lives. During their final semester, a distressed guardian overhears the student’s discussing their futures – the poignant and pathetic teenage prattle of optimism, fantasy and banal ambition – and admonishes them:

“None of you will go to America, none of you will be film stars. And none of you will be working in supermarkets as I heard some of you planning the other day. Your lives are set out for you. You’ll become adults, then before you’re old, before you’re even middle-aged, you’ll start to donate your vital organs. That’s what each of you was created to do . . . . You were brought into this world for a purpose, and your futures, all of them, have been decided.”

After leaving Hailsham, Kathy, Ruth and Tommy enter a haunted, attenuated adulthood, their friendship a shifting love triangle. They move into the “cottages” – (youth hostile, depressing, cold, damp) – halfway houses from which they make tentative steps into the real world and live in a prolonged limbo, waiting for the call to duty. Despite that fact that the students are interpellated as lesser beings, they are given vast amounts of freedom to explore the countryside, read books, watch movies, have sex. They live among older clones who, whenever the new students discuss an ordinary life – like a child fantasizes about defying reality to become a superhero, – react with contempt and imperiousness. The students are always aware of their predestined fate. There is no articulation to stumble upon. They are eventually called upon to serve one of two functions: act as a “carer” for those undergoing donations or enter into their first donation phase. Kathy is given a lengthy engagement as a “supreme carer”, a person capable of keeping the patients calm while organs are removed from healthy young bodies. With blind resignation, from one donation to the next, Kathy watches her friends break themselves against the inevitable, knowing that any day could be the day she’d get her own “notice” that she is to become a donor. Ruth is never a carer and put quickly into donations. A first generation sceptic – she suspects that she and her friends were copied from lowlifes, junkies and prostitutes – with vaguely articulated dreams that include no real quest for upwards mobility, only the illusion of privilege. When her search for her possible fails, she resigns herself to her ultimate fate, satisfied in having at least asserted privilege to her friends. When being cared for by Kathy, Ruth wants to only talk about Hailsham, remembering lessons timed so that “we were always just too young to understand properly the latest piece of information.” On her “completion”, marked by fatigue and defeat, Ruth is unable to conjure up any resistance other than the vague hope that Tommy and Kathy get a “deferral” (a special consideration afforded those  – who through true love, or art – deserve to be given “more time”).

By the time Kathy and Tommy hook up, Tommy has already begun his donations, their illusions nurtured in childhood lost, and the opportunity to realize their love, diminished. When Ruth urges them towards a “deferral”, Kathy experiences – for a moment – the possibility of a real life, with its attendant romance and independence and mystery. When her hopes of a  deferral are squashed (it was a myth), she remains stoic and accepting in the face of this crushing revelation and neither she nor Tommy – who erupts in a raving tantrum like those at Hailsham – can articulate their despair. Kathy is a successful product of Hailsham. Like Stevens, the ludicrously self-decepted butler in “The Remains of the Day”, her stoicism is rooted in her ingrained systems of behavior, rather than acquired systems of beliefs. Both of Ishaguros’ characters are completely accepting of the limitations of their own lives, their happiness restricted by status and fate. By preserving dignity at the expense of romantic love, Stevens who has no political wisdom and who is preoccupied with enforcing his own regimen of emotional repression, ultimately becomes aware of the lost potential of his life. After Tommy’s completion, Kathy accepts her own fate as a donor and her eventual death. Both characters are doomed – ensconced in British, myth-shrouded societies and questionable class divisions. Their passive complicity in their fates may seem frustrating to Americans whose cultural heroes tend to be those who escape terrible beginnings to rise above what society determines for them and become heroic in their toppling the hierarchies that seek to constrain them. There is no British Horatio Alger. The British are, well, different in that way. But isn’t there that thing that exists everywhere, for everyone, whatever our circumstances – that irreconcilable tension between our own hopes for happiness and the fear that you just can’t pull it off? Where every small surge of hope and courage is followed by a reluctance to face its implications for fear of being disappointed? That unfulfilled hope is always there so so is our fear of rebellion, even if we do succeed in doing it sometimes.

deferral are squashed (it was a myth), she remains stoic and accepting in the face of this crushing revelation and neither she nor Tommy – who erupts in a raving tantrum like those at Hailsham – can articulate their despair. Kathy is a successful product of Hailsham. Like Stevens, the ludicrously self-decepted butler in “The Remains of the Day”, her stoicism is rooted in her ingrained systems of behavior, rather than acquired systems of beliefs. Both of Ishaguros’ characters are completely accepting of the limitations of their own lives, their happiness restricted by status and fate. By preserving dignity at the expense of romantic love, Stevens who has no political wisdom and who is preoccupied with enforcing his own regimen of emotional repression, ultimately becomes aware of the lost potential of his life. After Tommy’s completion, Kathy accepts her own fate as a donor and her eventual death. Both characters are doomed – ensconced in British, myth-shrouded societies and questionable class divisions. Their passive complicity in their fates may seem frustrating to Americans whose cultural heroes tend to be those who escape terrible beginnings to rise above what society determines for them and become heroic in their toppling the hierarchies that seek to constrain them. There is no British Horatio Alger. The British are, well, different in that way. But isn’t there that thing that exists everywhere, for everyone, whatever our circumstances – that irreconcilable tension between our own hopes for happiness and the fear that you just can’t pull it off? Where every small surge of hope and courage is followed by a reluctance to face its implications for fear of being disappointed? That unfulfilled hope is always there so so is our fear of rebellion, even if we do succeed in doing it sometimes.

Tommy tells Kathy near his “completion”, that “you’d be the perfect one for me … if you weren’t you”, because what is defective in human relations, in ordinary human life – the distilled and persevering human essence that survives and insists on subtly expressing itself after you take away family, religion, cultural orientation, a past and possible futures – and shapes people into individuals – transcends science fiction and precedes cloning technology be eons. “Science-fiction” and the shadowy backdrop of genetic engineering are simply frameworks for an oblique and elegiac meditation on the nature of human relationships, with familiar tactics and preoccupations, the loss of childhood’s expectations, the desire to hold on to sentimental attachments forever and the steady erosion of hope. It is that kairotic moment in adolescence when self-knowledge brings intimations of one’s destiny, when the shedding of childhood’s cloak of safety and wonder can lead to disillusionment, debilitation, drugs, rebellion, newfound resolve or an ambivalent acceptance of a predetermined fate.

After her friends have died, Kathy has a nostalgic impulse to drive around, looking for where Hailsham once stood. It has long since closed, a grotesque reminder of the deception and the failed “experiment” and she can never quite make out the spot where it stood, it could be any of the same seeming stretches of bland countryside. This particular boarding school fantasy has no ponies or clattering hockey sticks. It is so mundanely told and  deliberately grounded, it’s a strain to grasp – through it’s inky bleakness – the inevitable link between present and past and the perilous impact of nostalgia. A dying young man in Kathy’s care asks to hear stories of Hailsham  – which cements Kathy’s nostalgic notion that she and her friends were “lucky” to have had Hailsham. The patient, like most other clones, was not lucky enough to have been raised in humane conditions:

“What he wanted was not just to hear about Hailsham, but to remember Hailsham, just like it had been his own childhood. He knew he was close to completing and so that’s what he was doing: getting me to describe things to him, so they’d really sink in, so that maybe during those sleepless nights, with the drugs and the pain and the exhaustion, the line would blur between what were my memories and what were his. That was when I first understood, really understood, just how lucky we’d been — Tommy, Ruth, me, all the rest of us.”

I heard someone say about the book “why didn’t they just run away? as if the novel was a failed martian story, a lessor form of some Hollywood movie I’ve never heard of, and that the author missed the point. Maybe it’s because it’s a throw back to the New Wave and things like “inner space” over “outer space”, allegorical settings over scientific accuracy or plausibility, what Harlan Ellison promoted as “speculative fiction”, and cautionary language about the progress of science handed down from Mary Shelley, Edgar Allen Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Ira Levin are all outdated and we’ve swung back around to aliens with giant noggins. And maybe it’s less meaningful or cautionary so far removed from real life context – Tuskegee, Â nuclear bombs. Yes, vague questions float in – for whom are the organs intended in a society that seems not much different than ours? What exactly is being donated? But those questions are unimportant and are never answered, reflecting the blindness of people who “preferred to believe these organs appeared from nowhere, or at most that they grew in a kind of vacuum.”

There are no “good” or “bad” people to the students – the guardians who technically are their “oppressors”, are the same people that gave them life, care for them, encourage their talents  and allow them to live. The students love their guardians and have no identifiable enemy. There is only clone or not clone, and that is what defines their reality. Their fate is inevitable – the discourse having been strongly sedimented in and excludes any other. They are not like human slaves, able to educe ideas of emancipation, because the clones do not see themselves as humans they are, simply, students. They have a small degree of agency and maneuverability that allows them to articulate minor modifications to their lives – Ruth’s dream to “work in an office”  – but not to reach beyond it. It would be up to external forces, like the guardians, to articulate another path. But Hailsham is merely a humanitarian experiment set out to prove that students have souls, and as Miss Emily explains to Kathy and Tommy – vanquishing their last hope, the only hope they have ever known – the human incentives for the donations system were simply too great. The “normals” needed their kidneys and lungs, particularly  in light of the Morningdale scandal, which presented the prospect of biologically altered super-clones. In the end, society chose to look the other way and the Hailsham experiment was deemed a failure, leaving Miss Emily with only this small consolation for Kathy and Tommy: […] ..the memories, I suppose, of all of you. And the knowledge that we’ve given you better lives than you would have had otherwise.

and allow them to live. The students love their guardians and have no identifiable enemy. There is only clone or not clone, and that is what defines their reality. Their fate is inevitable – the discourse having been strongly sedimented in and excludes any other. They are not like human slaves, able to educe ideas of emancipation, because the clones do not see themselves as humans they are, simply, students. They have a small degree of agency and maneuverability that allows them to articulate minor modifications to their lives – Ruth’s dream to “work in an office”  – but not to reach beyond it. It would be up to external forces, like the guardians, to articulate another path. But Hailsham is merely a humanitarian experiment set out to prove that students have souls, and as Miss Emily explains to Kathy and Tommy – vanquishing their last hope, the only hope they have ever known – the human incentives for the donations system were simply too great. The “normals” needed their kidneys and lungs, particularly  in light of the Morningdale scandal, which presented the prospect of biologically altered super-clones. In the end, society chose to look the other way and the Hailsham experiment was deemed a failure, leaving Miss Emily with only this small consolation for Kathy and Tommy: […] ..the memories, I suppose, of all of you. And the knowledge that we’ve given you better lives than you would have had otherwise.

Besides, it’s not like the author is unaware of what he is doing. Kathy and Tommy cling to the possibility of a “deferral”, but never consider to vanish into the world of freedom that they view from a distance. They hike through woods and barbed wire and lay gaze on a “boat” as if it were a fantastical oddity. They love the movie “The Great Escape”, the moment the American jumps over the barbed wire on his bike….

“If you’re to have decent lives, you have to know who you are and what lies ahead of you”, the children at Hailsham are told. Yet they comprehend it only abstractly and distantly, just as ordinary, young, healthy people comprehend death — something inevitable, but still unthinkable. We grow up, if we’re lucky, safe and hopeful and are slowly made aware of the grotesque fact of our end. When I was a nanny, my 3 year old charge was shaken and morose when, after learning the fate of the dinosaurs, asked the inevitable question “But PEOPLE don’t die, right? ….” We are all guilty of a collective acceptance and unconditional devotion to our fates. By foreshortening the students lives and hideously constraining their chances of happiness, the story evades banality and slams us up against a raw confrontation with death, loss, the destruction of what once was valued. Modern desperation regarding aging and death, plastic surgery and plastic hearts, advancements in medical science to offer us protection through everlasting biological health and the seemingly boundless human capacity for evasions and self-serving fictions is always bested. The clones have been created to satisfy the gluttonous human desire to postpone death, and rather than deconstructing this desire, the lives of Kathy, Ruth and Tommy further affirm it: They want to protect the things they hold dear, too. The modern world didn’t invent planned obsolescence, nature did. Kathy’s monstrous world of “caring”, “donating” and “completing” is anyone’s world – our modern, meaning-displaced lives, lived at half-power, dilatory, wasting, as if every day were not another day nearer to the end. There is no “alternate reality” at all, just one reality, just our own. We’re none of us built to last. Like someone said 1800 years ago, all things fade away – for the ones who “blazed once like bright stars in the firmament” and become the stuff of legend, they are buried in oblivion and rest of us, as soon as a shovel of earth is tossed on our corpses, we are ‘out of sight, out of mind.’

A little while and thou shalt be burnt ashes or a few dried bone and possibly a name, possibly not a name even….And all that we prize so highly in our lives is empty and corrupt and paltry, and we but as puppies snapping at each other, as quarrelsome children now laughing and anon in tears. trans.

So I never wondered why Kathy, Ruth and Tommy didn’t keep running, run to the docks, and paddle off, or why they don’t erupt with the fear and horror of their situation. What I wondered – and I didn’t like it – is why don’t we erupt with the molten rage of someone cast a terrible fate? Why don’t every single one of us who wake up every morning abject and breaking in turmoil and molten rage over the incomprehensible, completely personal sense of the inconclusiveness, the futility and exiguity of our existences, knowing that we will not have mattered, and that our lives, no matter what we have done or who we have been, will end having never been what they could have been.

In the novel’s final paragraph, Kathy looks at a field, facing her losses and her own death with stoicism, resolution and blind dignity. She describes a flat, windswept field with a barbed wire fence where all sorts of rubbish had caught and tangled. She imagines Tommy appearing here in spot where everything I’d ever lost since my childhood had washed up.

“if I waited long enough, a tiny figure would appear on the horizon across the field, and gradually get larger until I’d see it was Tommy, and he’d wave, maybe even call. The fantasy never got beyond that — I didn’t let it — and though the tears rolled down my face, I wasn’t sobbing or out of control. I just waited a bit, then turned back to the car, to drive off to wherever it was I was supposed to be.”

Kathy’s story is so harrowing and upsetting, the images of odd beauty and mounting existential distress so blinding, that it ate at me for months. Because it isn’t a story about clones paddling off an island, away from a surgeon with a kidney scalpel. It is about me. It’s about what comes creeping into my mind in those few moments I forget to be distracted. It’s about repressing what we all know, that horrible thing that is the same for all of us, through the same evocation of the same pervasive menace, made up of allusions and stories and the shadows of things hinted. It’s about knowing that in this life people give in, fail one another, grow old and fall to pieces. It’s about knowing that no matter what we do, the unendurable fragility of everything we love the most and the promises we made to ourselves and to each other, to hold on to, to never let go of, are all reduced to nothing, to detritus cast on the wind. It’s about what’s identified as the greatness in a human being “that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Bear what is necessary, don’t conceal it- all idealism is mendaciousness, in the face of what is necessary. Accept your fate” – but that accepting won’t change a fucking thing. Beneath Kathy’s flattened and phlegmatic emotional landscape, her blank stoicism as she casts gaze over the empty field where she stood with her friends, she is neither calm nor stoic but rather breaking in turmoil, ululant with the unexpressed yet perfectly articulated rage of a person undisputedly endowed with- whatever is meant physically, spiritually, or metaphorically by – a “soul”.

“..look at the immensity of time behind thee, and to the time which is before thee, another boundless space. In this infinity then what is the difference between him who lives three days and him who lives three generations”? (marcus aurelius, meditations IV. 33, trans. Scot and David Hicks)

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro, Publication date: April, 5, 2005, Knopf Publishing Group/304 pp.

illustrations from boarding school series books via Enid Blyton.net