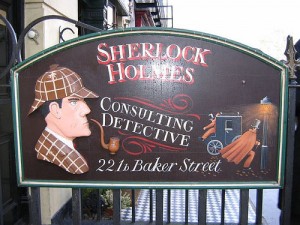

The quintessential “faux literary home” is that of fictional super sleuth, Sherlock Holmes: The Sherlock Holmes Museum of Baker Street. Here at 221b Baker Street, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson – but not Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – “lived” from 1881-1904. The address is a shrine for devotees but didn’t actually exist until an enterprising businessman with a million dollar idea bought the broken down Georgian boardinghouse at 239 Baker Street, altered the address, and converted it into this museum/gift shop/house pastiche in 1989. Not a home and not a museum…but something, an endless expanse of kitsch, props and hyperreal meaninglessness utterly devoid of actual significance or historical fact. Embrace the absurdity and buy a lot of souvenirs and it’s worth the trip.

Greeted by a jaunty, fake London bobby who patrols the stoop (and never broke character except when he obliged to take our picture), then carefully count the 17 steps into a parlor filled with shabby, anachronistic furniture and junk. The 4 story townhouse is a room by room crap barrel of props, lurid dioramas and wax mannequins, who are either reenacting murdes scenes in victorian studies or skulking on stairwells and behind doors.

I am reasonably well associated with the Holmes canon and I can say that the stuff reasonably represents those in the stories. From The Adventures of the Empty House we see the chemical corner with the acid stained deal-topped table, the diagrams, the violin case, the pipe rack and the persian slippers. Watson’s bedroom is cluttered with medical paraphernalia, journals, locks, bunsen burners, beakers, weighty medical tomes and case notes.

All the rooms hold a hoarder’s delight of sleuthing stuff and victorian era bric-a-brac; ashtrays, magnifying glasses, clabash pipes, violins, chemistry equipment, drug paraphernalia, persian rugs and slippers, eyeglasses, magnifying glasses, field books, periscopes, telescopes, notebooks and diaries, walking sticks, revolvers and weapons, sepia photos, portraits, hats and disguises. There are also several hilariously lurid crime scenes played out in elaborate dioramas with dolls and miniatures.

A photo of Irene Adler, “the daintiest thing under a bonnet on this planet”, who out-wits Holmes in A Scandal in Bohemia sits on a mantle. The photo was left behind after she took flight. Holmes was given the photo as payment for his service in the case, and it remained one of his most prized possessions. Irene had “the face of the most beautiful of women, and the mind of the most resolute of men”.

A photo of Irene Adler, “the daintiest thing under a bonnet on this planet”, who out-wits Holmes in A Scandal in Bohemia sits on a mantle. The photo was left behind after she took flight. Holmes was given the photo as payment for his service in the case, and it remained one of his most prized possessions. Irene had “the face of the most beautiful of women, and the mind of the most resolute of men”.

Another highlight is a shadow box holding the gruesome shrunken Voodoo fetish from The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge and the bulldog revolver smartly concealed in a bible from “The Solitary Cyclist“ is exciting if you are a fan of such delightful little things like secret hiding places in fake books.

Crucially, the Sherlock Holmes House has the mother of all gift shops, a one stop shop for all Holmsian crap and ephemera: Key rings, coins, shot glasses, mugs, money clips, wallets, posters and prints, canes, umbrellas, books, cds, tobacco tins, matchbooks, handcuffs, cufflinks, bookmarks, spoons, oven mitts, t-shirts, scarves, pens, stuffed bears with sleuthing hats, teapots, busts, a respectable assortment of magnifying glasses and curly calabash pipes, and woefully overpriced but absolutely necessary houndstooth deerstalker hats.

The best and worst thing about the museum are the visitors who think they are actually roaming and snooping around Holmes’ house, that he actually lived here – a tribute, I guess, to the fact that Doyle was able to create such a believable hero, but alarming nonetheless. At the time that Sherlock Holmes was skulking around and dusting for prints, 221B Baker Street didn’t even exit. But since then it has been created, further confusing an already befuddled fan base. The fictional characters Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson have transcended legendary literary world status to the extent that they have, in over 50% of Brit’s eyes (hence then probably 80% of Americans), become real characters who actually lived and worked in London during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. That is what makes this simulated house museum so weird.

When a beleaguered Doyle threatened to kill the character off (so that he could write “serious” fiction), – in The Final Problem – by having Professor Moriarty send him to his death over the Reichenbach Falls, newspapers actually ran headlines about Holmes’s death, and mourners walked the streets sobbing and wringing their hands.