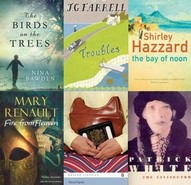

The shortlist for The Lost Man Booker Prize – a one-off prize to honour the books published in 1970 that were not eligible for consideration for the Booker Prize – was announced last week. The six books on the list are:

• The Birds on the Trees by Nina Bawden (Virago)

• Troubles by J G Farrell (Phoenix)

• The Bay of Noon by Shirley Hazzard (Virago)

• Fire From Heaven by Mary Renault (Arrow)

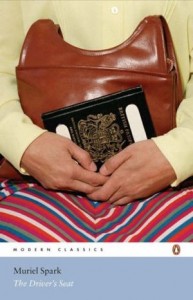

• The Driver’s Seat by Muriel Spark (Penguin)

• The Vivisector by Patrick White (Vintage)

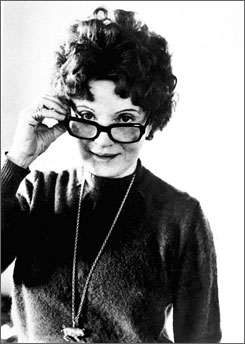

Sadly, four of the six authors on the list are dead: J.G. Farrell died in 1979, Mary Renault in 1983, Patrick White in 1990 and Muriel Spark died just 4 years ago, in 2006. Muriel Spark is one of Britain’s grand dames of literature and one of my all time favorite authors. She is shortlisted for her masterpiece of modern weirdness, The Driver’s Seat. When I saw the cover of the new Penguin edition – which somehow captures her odious essence so perfectly – the memory of the Driver’s Seat and it’s queerly creepy heroine came flooding back.

Lise.

Her name evokes the same creepy crawlies as the name Eunice Parchmen, the spooky illiterate from Ruth Rendell’s A Judgement in Stone. Yes, one is a murder victim and the other a cold-blooded slaughterer of families, but both women creep me out in the same way. Masterfully creepy “metaphysical thriller” The Driver’s Seat must have been the best book of 1970. The first genius of the book is it’s stunning originality; it only makes sense backwards. Muriel Spark described Driver’s Seat as a “whydunnit” because one chapter in, she reveales that the protagonist, Lise, is going to be murdered.

She will be found tomorrow morning dead from multiple stab wounds, her wrists bound with a silk scarf and her ankles bound with a man’s necktie, in the grounds of an empty villa, in a park of the foreign city to which she is traveling on the flight now boarding at Gate 14.

“Dark” doesn’t being to describe this book. It’s only 100 pages long, pared down to the bare minimum numbers of words. It’s such a surgical masterpiece of plotting and suspense that it boggles my mind that it could be achieved in so few words. I read The Driver’s Seat in one sitting, a frown on my face and my hands gnarled into balls. The novel is a macabre cartoon and the grimmest of Muriel Spark’s sardonic artist’s parables. She manages to be both obsessive and droll in chronicling her heroine’s story. The narrative voice is a chilling combination of an icy detachment and an ironic self-consciousness. Lise is a (34 year old) spinster, working in an accounting firm somewhere is Northern Europe. She is neither “pretty nor ugly” and acts so oddly and erratic it is squirm worthy.

The book begins with Lise in a dress shop changing room, shopping for her impending holiday of a lifetime. She chooses a chimeric traveling outfit, a hideously garish dress with “a lemon-yellow top with a skirt patterned in bright V’s of orange, mauve and blue” and a red and white candy cane striped coat. Her co-workers sit, silently, as she describes it to them in between guffaws of barking laughter and tears:

The colours go together perfectly. People here in the North are ignorant of colours. Conservative; old-fashioned. If only you knew! These colours are a natural blend for me. Absolutely natural.

Lise’ queerness, the strained, off-kilter encounters and weirdly inappropriate conversations, her off-putting behavior, and unprovoked mania suggests that she may be hurtling towards a mental breakdown. The possibility of her having had a crack-up in the past is alluded to (a “month’s off for illness”). She is on paper a ploddingly regular person, but off paper some sort of monster. Not a killer monster, just a tragically monstrous regular person. To drive this point home, Muriel Spark gives Lise a parodically ghoulish hairdo, skunk-striped and heaped on her head like the goddamn Bride of Frankenstein. Somehow Lise has kept a job for 16 years which makes you doubt your instinct that she is actually as crazy as Spark is leading you to believe. And her apartment is spic and span, her “pine box”, where “everything is contrived to fold away into the” dignity of unvarnished pinewood”, perfectly organized and devoid of tchokes or personal touches. How crazy could she be? (insert inappropriate, barking laughter).

Lise gives herself a ghoulish makeover and emerges a giggling sexpot, a beast in garish clothing. She embarks on her “holiday of a lifetime”, largely to prowl for sex (“If he’s my type,” she says, “I want to meet him.”), but also for some sort of non specific adventure, an end to “the lack of an absence”. She shops at the airport for a book that is “predominantly pink or green or beige” to match her colorful traveling outfits. Through a series of chilling and grotesque pastiches of literary cliches—the lonely, single girl on holiday on the prowl for her dream man, the Jacobean death drama, with its terrible, darkly comic and inevitable end – Lise stumbles and fumbles her way through an unnamed European city, clopping around the streets, drawing stares and alarming strangers. She carries around the “prop” book with it’s brightly colored jacket, that she flashes from time to time as though she were on a secret mission and trying to signal an agent. At one point, Lise describes the prop-book as “a whydunnit in q-sharp major and it has a message”. Alas, her search for adventure and the obsessional experience turns a corner into nihilistic darkness and she hits an inceberg of self-destruction. When she finally meets her predestined end, which is pitiful, ghastly and violent, you are scared, sad, confused, depressed, self-loathing, abject.

After having spent so much time with this odious character of her own creation, and finishing the book, Spark flew into a wild depression and panic, landing in the hospital, apparently suffering from some sort of nervous exhaustion/breakdown. Lise will do that to a person.

The Lost Man Booker was created in 1971 when it was realised that the Booker Prize ceased to be awarded retrospectively and became – as it is today – a prize for the best novel of the year of publication. The panel of three judges, all of whom were born in or around 1970, considered 21 titles, among them some of my favorite authors; Melvyn Bragg for A Place in England, Iris Murdoch’s A Fairly Honourable Defeat and Len Deighton for Bomber. Lastly, the mother of all grande dames of British literature, the incomparable Ruth Rendell, was longlisted for her brilliant, Inspector Wexford investigates-a- sexless-marriage- in-the suburbs-murder-mystery, A Guilty Thing Surprised.

The winner will be announced on 19 May 2010. It better be The Driver’s Seat. Or Lise will getcha.