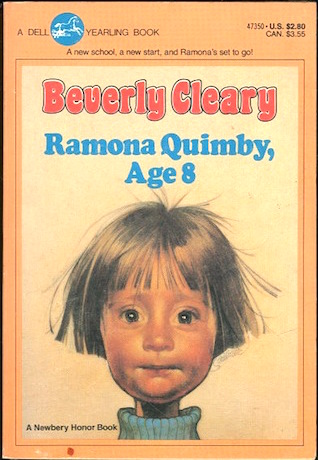

Beverly Cleary, who turned 100 last week, has written more than three dozen children’s books over the course of her life, starting with her first book, “Henry Huggins”, in 1950. Cleary was working as a librarian when a group of little boys complained to her that he couldn’t find any books about “kids like us.” hence, Cleary, a hater of didactic literature, birthed Henry Huggins, of Klickitat Street in Portland, Ore.

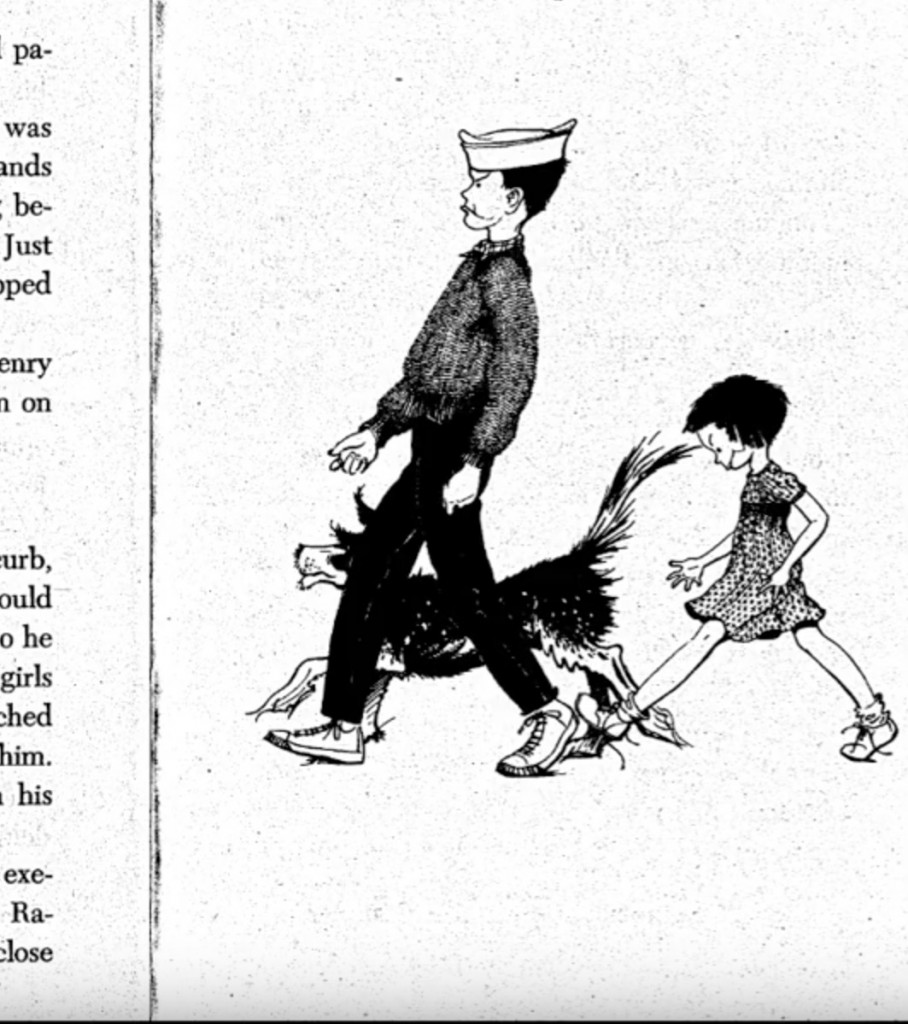

Henry had a best friend named Beezus and a mischievous but lovable little sister Ramona Quimby. The earlier books in the series tend to be written from Henry’s point of view, and the later ones from Ramona’s; there is also one where the protagonist is Ramona’s sister and one told from the POV of Henry’s dog. I’ve read them all, most multiple times.

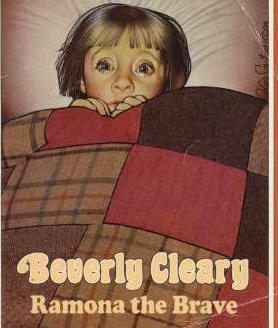

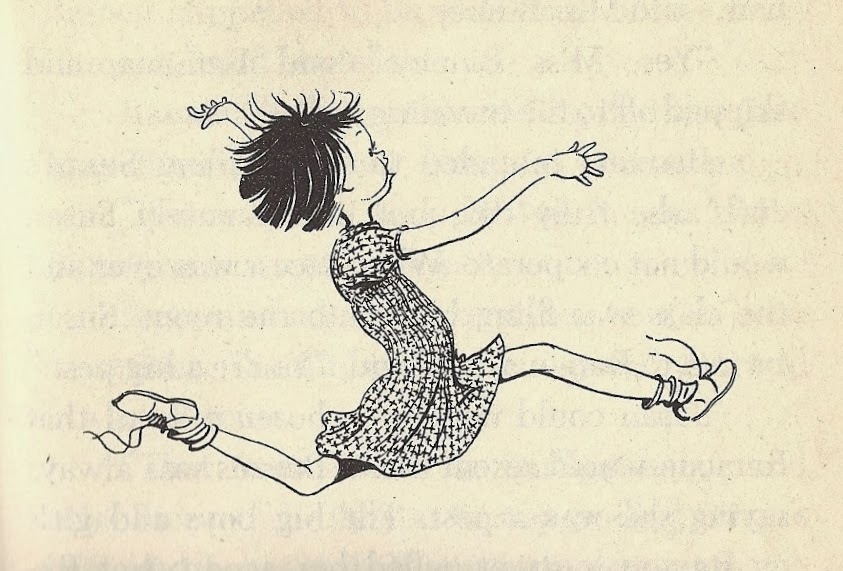

Ramona was my favorite, naturally. I loved that lovable, short-haired little weirdo. Beverly Cleary took her all the way from nursery school to the fourth grade. Cleary says when she was writing Ramona, she took inspiration from a little girl who lived in the house behind her as a child.

“She had been sent to the neighborhood store for a pound of butter,” Cleary told NPR in 2010. “In those days, it was all in one piece, not in cubes. And she had opened the butter and was eating it.”

This is exactly how I felt, 99% of the time.

“GUTS GUTS GUTS!”

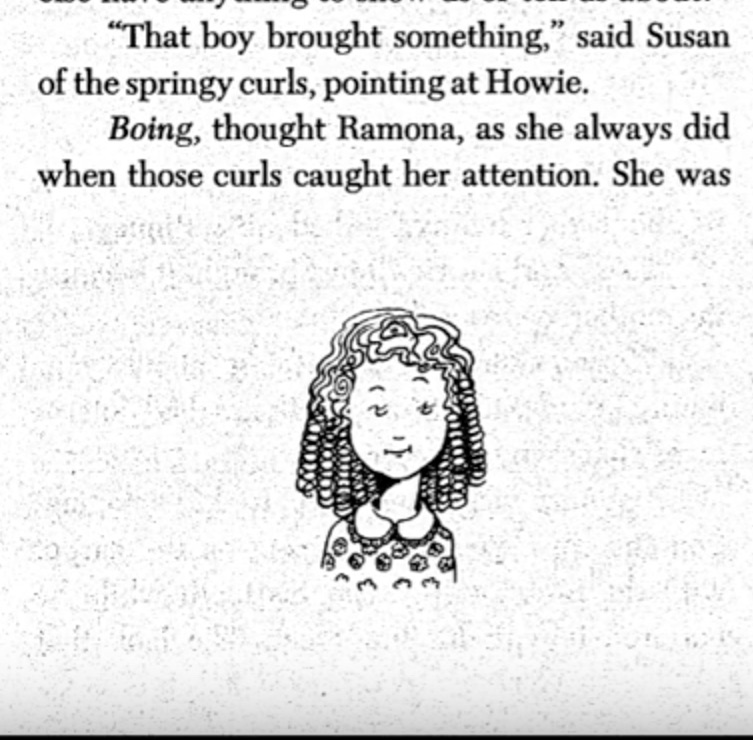

I remember vividly Ramona’s fascination with sloppy Willa Jean and Susan, who had hair like she read about in “old fashioned books”, that was reddish gold and hung in ringlets that touched her shoulder, bouncing when she walked. I had the same fascinating with N ellie Olsens’ bouncy hair in the Little Hosue books. Ramona was fascinated by Susan’s hair and fantasized about the cartoon BOING! sound the hair would make when she it pulled one of Susan’s curls.

ellie Olsens’ bouncy hair in the Little Hosue books. Ramona was fascinated by Susan’s hair and fantasized about the cartoon BOING! sound the hair would make when she it pulled one of Susan’s curls.

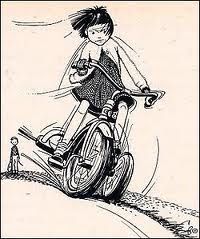

Labeled a “PEST” by her older sister Beezus (Ramona couldn’t pronounce her real name, Beatrice, so now everyone called her Beezus, one reason she may had had a grudge against her little sister), Ramona Quimby is plucky and talkative, prone to missteps and humiliations. She tried to crack a hard-boiled egg on her head at school, but the egg wasn’t hard-boiled, and she literally ended up with egg on her face. She drops out of kindergarten, squeezes a tube of toothpaste down a sink, rides a tricycle around the living room while playing a single note on her harmonica, and makes tin-can stilts with a friend and clatters around the neighborhood joyfully singing “One Hundred Bottles of Beer on the Wall.” She is impatient, ” a girl who could not wait.”

Labeled a “PEST” by her older sister Beezus (Ramona couldn’t pronounce her real name, Beatrice, so now everyone called her Beezus, one reason she may had had a grudge against her little sister), Ramona Quimby is plucky and talkative, prone to missteps and humiliations. She tried to crack a hard-boiled egg on her head at school, but the egg wasn’t hard-boiled, and she literally ended up with egg on her face. She drops out of kindergarten, squeezes a tube of toothpaste down a sink, rides a tricycle around the living room while playing a single note on her harmonica, and makes tin-can stilts with a friend and clatters around the neighborhood joyfully singing “One Hundred Bottles of Beer on the Wall.” She is impatient, ” a girl who could not wait.”

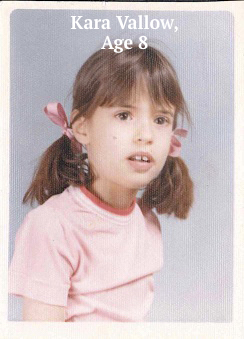

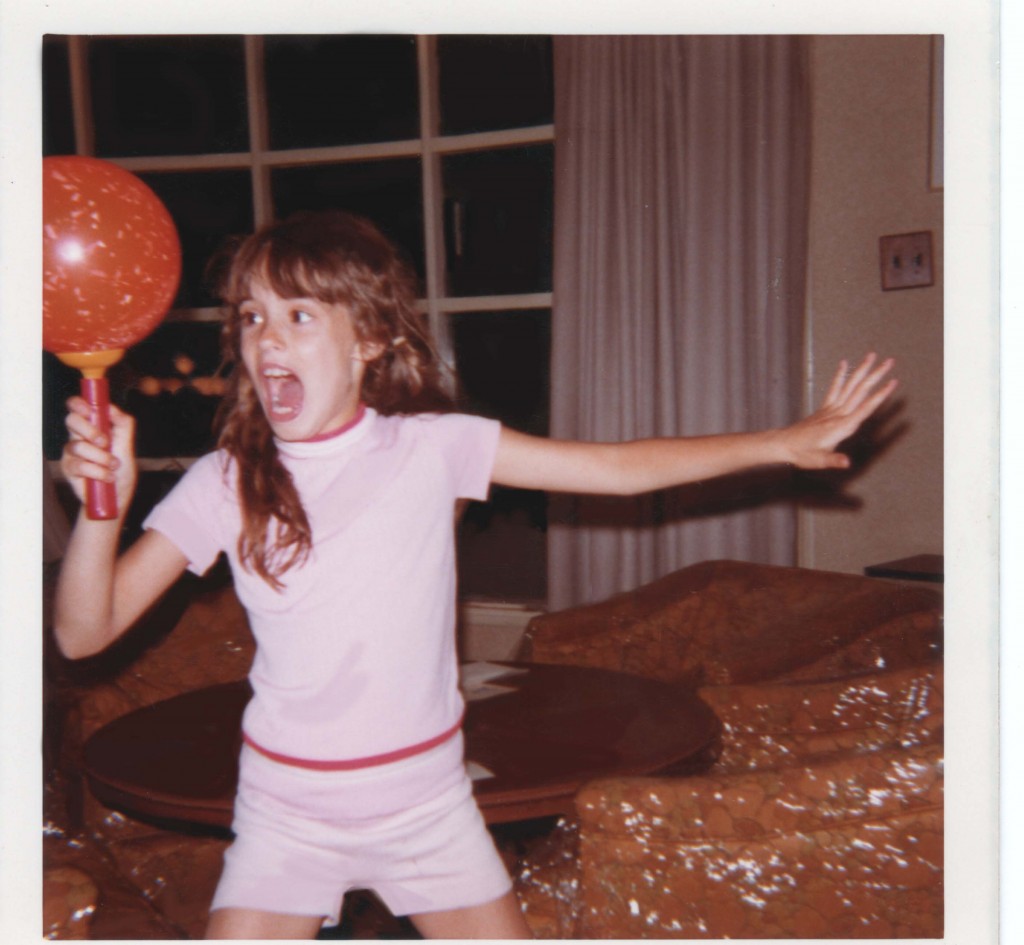

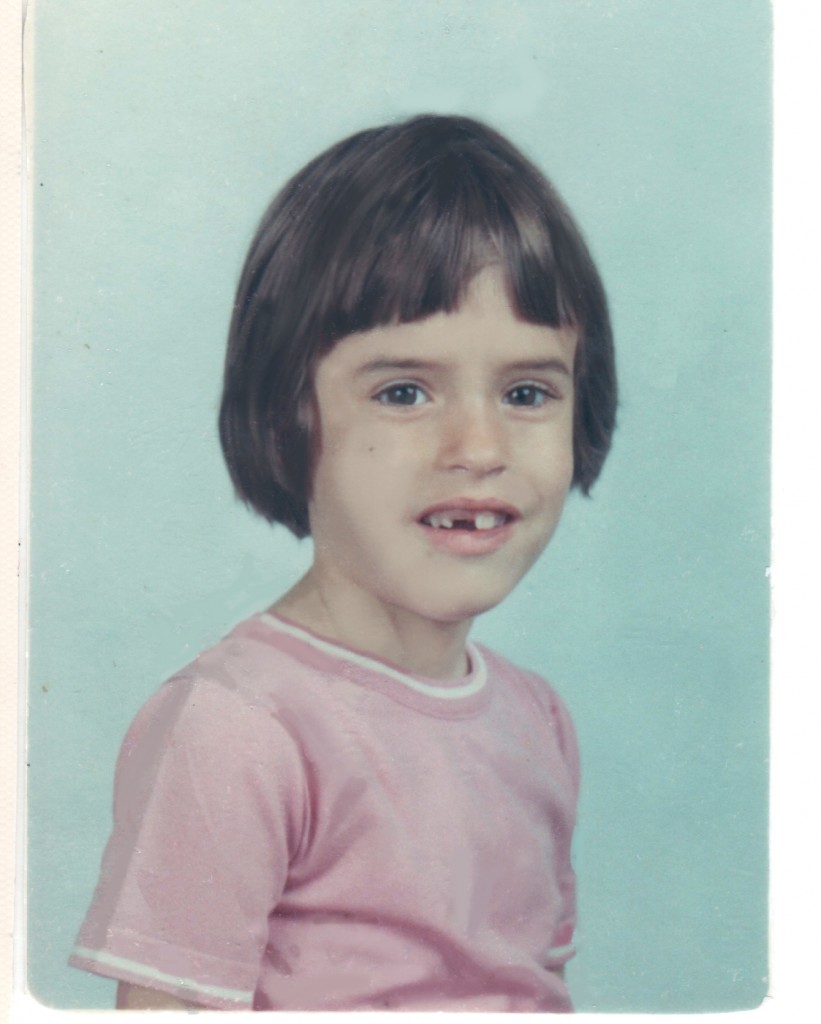

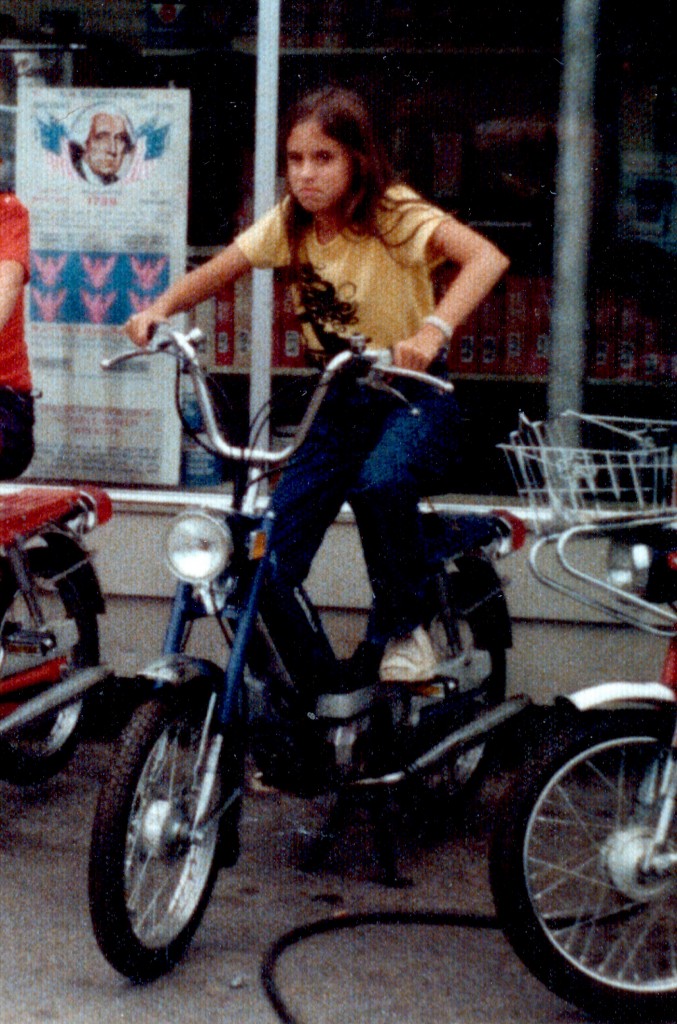

At 8-years old, I was mosquito-sized, messy, had a horrible haircut and lived my childhood with a kind of cartoony, preternatural intensity. I was weird and maybe even a little out of control.

Here I am leading some nonsense around the neighborhood, for no reason.

Beverly Cleary’s books are notable for their realistic depictions of ordinary children, of “kids like us”, and her have remained weirdly popular, even as recent children’s and young-adult books seem to be all driven by the dreaded fantasy, the supernatural, and magic. Cleary’s genius and charm is largely rooted in her intense absorption in the quotidian emotions and nonevents of kid life, the way she fully and leisurely enters and articulates the inner life of a kid’s mind.

The early editions depict a childhood world now outwardly gone, where the kids have the run of their humble, middle-class neighborhood, unsupervised by adults, and where dogs, unencumbered by leash laws, walk their kindergartners to school. In addition, the distinguished, offhandedly charming illustrations in the original editions, by Louis Darling, depict plainly dressed, crew-cut, unmistakably mid-20th-century children, and a Ramona who, true to Cleary’s stroppy character, somewhat resembles a wild child. Naturally, they have been updated a lose a lot of the charm in the process. Now get off my lawn.

Now 100, Cleary is retired and so we won’t be seeing another Ramona book. But Cleary thinks Ramona will “be all right” when she grows up.

“She’ll do something creative. She liked to draw because her father liked to draw. Children often live out their parents’ frustrations. But I don’t know. I’d have to write the book to find out.”