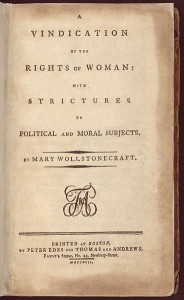

If you are going to only read one weighty tome this National Women’s Month, try this one, written 218 years ago. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects written in 1792 by British philosopher, travel writer, novelist and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft is one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy and one of the most original books of the 18th century. In it she argues that women are not naturally inferior to men, but appear to be because they lack education, and that both men and women should be treated as equal, rational beings. It’s said that Mary wrote to relieve her wounded spirit. She had a difficult childhood, the victim of poverty and an abusive, alcoholic father. From an early age, Mary decided, “I must be independent and earn my own subsistence or be very uncomfortable.â€

Uneducated but ferociously auto-didactic (she was no “Bluestocking”), Mary believed in defining femininity and marriage for herself. Both of Wollstonecraft’s two novels criticize what she viewed as the patriarchal institution of marriage and its deleterious effects on women. In her first novel, Mary: A Fiction (1788), the heroine is trapped in a loveless marriage and finds love and affection with two passionate romantic friendships, one with a woman and one with a man. Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman (1798), an unfinished novel published posthumously and considered Wollstonecraft’s most radical feminist work, tells the story of a woman imprisoned in an insane asylum by her husband, where she has an affair with a fellow inmate.

Mary’s first published work (in 1787) was an early version of the modern self-help book, Thoughts on the education of daughters: with reflections on female conduct, in the more important duties of life. Thoughts was a “conduct book” that offers advice on female education to the emerging British middle class.The book was not successful, and was not republished until the rise of feminist literary criticism in the 1970s.

A “hyena in a petticoat” is how Horace Walpole described Mary Wollstonecraft. Many more were even meaner. I was sad to read that she was pilloried by, among others, Maria Edgeworth, whose work I love. Apparently she patterned the outlandish and “freakish” Harriet Freke in Belinda (1801) after Wollstonecraft.

Mary’s great love affair was with Gilbert Imlay, an American merchant and author of A Topographical Descriptions of the Western Territory of North America (1792) and The Emigrants (1793). Imlay caused Mary an enormous amount of anguish through his apparent lack of passion for her, his infidelity, and ultimately his complete rejection of her, even though she was pregnant with his child. A year after the baby’s birth Wollstonecraft attempted suicide twice by taking laudanum. Afterwards, she wrote: “ I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery”. Soon after, she met William Godwin, her future husband.

Wollstonecraft died at the age of thirty-eight, ten days after giving birth to her second daughter, Mary. Too much information: Her placenta never came out and a doctor was forced to take out the broken pieces by hand. The procedure, without any painkillers, took several HOURS. The doctor did not sterilize his hands or equipment causing a massive infection. After ELEVEN days of excruciating pain and agony, Wollstonecraft died of septicaemia (referred to hen as “childbed fever”)! Mary’s slavishly devoted husband Godwin wrote: “I firmly believe there does not exist her equal in the world. I know from experience we were formed to make each other happy. I have not the least expectation that I can now ever know happiness again.” Their baby, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, lived. She would later write under the name Mary Shelley, best known for the Gothic masterpiece Frankenstein.

After Wollstonecraft’s death, Godwin published a Memoir (1798) of her life, which inadvertently destroyed her reputation for a century. The world was horrified that Godwin would reveal Wollstonecraft’s unorthodox lifestyle, her love affairs, her illegitimate children, and suicide attempts. Writers steered clear of her work and she was rarely quoted or referenced. Poor Godwin, he well meaning and honest memoir nearly caused the complete intellectual loss of his wife’s ideas. The poet Robert Southey accused him of “the want of all feeling in stripping his dead wife naked” and satires such as the vicious The Unsex’d Females ( “unsex’d” meaning violating what he defines as women’s proper role), were published. These views of Wollstonecraft were perpetuated throughout the nineteenth century and resulted in poems such as “Wollstonecraft and Fuseli” by Robert Browning and that by William Roscoe which includes the lines:

Hard was thy fate in all the scenes of life

As daughter, sister, mother, friend, and wife;

But harder still, thy fate in death we own,

Thus mourn’d by Godwin with a heart of stone.

When the feminist movement started to heat up at the turn of the twentieth century, Wollstonecraft’s advocacy of women’s equality and critiques of conventional femininity became increasingly relevant. Commentators have looked at A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in its historical and intellectual context rather than in isolation or in relation to subsequent feminist theories. She is no longer seen as just Mary Shelley’s mother, a scandalous literary figure, or the embodiment of a nascent feminism which only was deemed relevant two hundred years later, but as an Enlightenment moral and political thinker.

“It appears to me impossible that I should cease to exist, or that this active, restless spirit, equally alive to joy and sorrow, should be only organized dust — ready to fly abroad the moment the spring snaps, or the spark goes out, which kept it together. Surely something resides in this heart that is not perishable — and life is more than a dream. “- Mary Wollstonecraft