by Andrew DeGraff

Product details: Hardcover: 128 pages

Publisher: Pulp; Original edition (October, 2015)

Language: English

ISBN-13: 978-1-936976-86-7

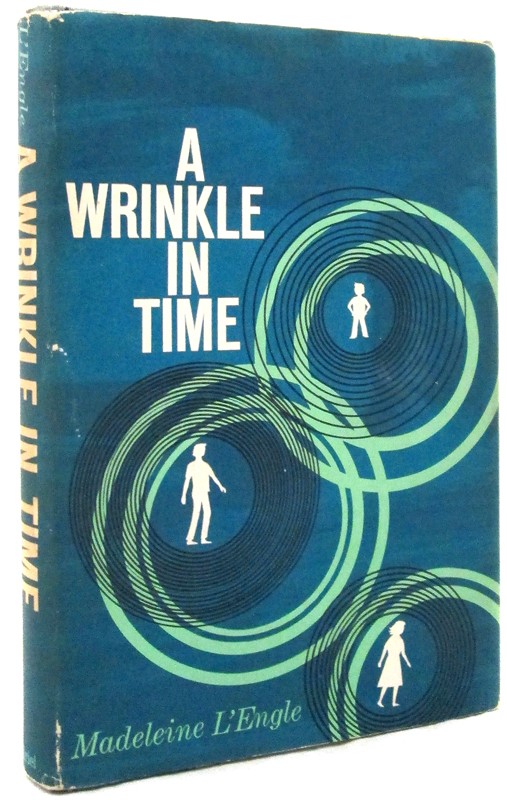

The 1963 Madeleine L’Engle classic, A Wrinkle in Time was one of my favorite books from childhood. Alongside the Narnia Chronicles. it was as close to sci-fi as I was going to get.

This was what my copy looked like:

Disclosure: I am a vicious judger of books by their coverer and always was. Needless to say, this was not appealing to an 8-year-old me. A trio of pale-green concentric circles that looked like goddamn radio waves, against a dark, storm blue background. The three silhouettes not saying ANYTHING about the characters that I may or may not be reading about in the book.

What the hell was this? Too sic-fi, too weird, too psychedelic.

Turns out, it is the story about a 12-year-old girl, Meg and her little brother Charles who live in the requisite big, drafty New England house on a wooded hill, with parents who are brilliant scientists, the mom a beautiful one. Meg is messy, not pretty, temperamental, and surly. She fights with the school bully to protect her little brother. The time-traveling part comes in when the children need to search for their father, who has disappeared – “through a wrinkle in time, to the deadly unknown terrors beyond the tesseract!”

If I had not gotten past that cover, I would have never given myself entree in science fiction and would have missed out on The Lord of the Ring Books which gave way

(I remember this edition, a more lurid fantasy attempt to broaden its appeal).

In the covers and illustrations between the pages of many of the books I read, the writers have a way of conveying to their readers exactly where their characters are in a given time and place. It’s not always easy to paint the mental picture you want if the drawings are skimpy, unadorned sketches , or if the narrative is complex, or if the writer has built a world that is incomprehensible in scope. But I always made the mental effort of conjuring up what places looked like.

What does the town in Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” look like? What about the Castle Elsinore in Hamlet? Or Odysseus’ path in Homer’s Odyssey? Or the New York of Invisible Man? But what about some more complex literary habitats? How would you draw a map of the place where Vladimir and Estragon wait for Godot? Or delineate the routes to love and/or social standing in Austen’s Pride and Prejudice? Retrace Frederick Douglass’s escape from slavery into his prominent role in shaping the national discourse? The flat Earth of Around the World in Eighty Days or the many Londons of A Christmas Carol? How might a map of Moby-Dick look? Would it follow the Pequod around the North Atlantic? Envision a visual depiction of Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges’ infinite labyrinthine library from The Library of Babel or Huckleberry Finn’s adventurous route through the lush Mississippi delta?

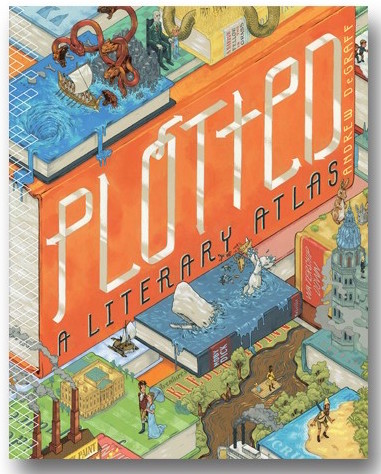

I just picked up a book called Plotted, a collection of stunningly detailed incredibly wide-ranging maps all inspired by literary classics, re-engaging readers with a canonical text. One of which is A Wrinkle in Time.

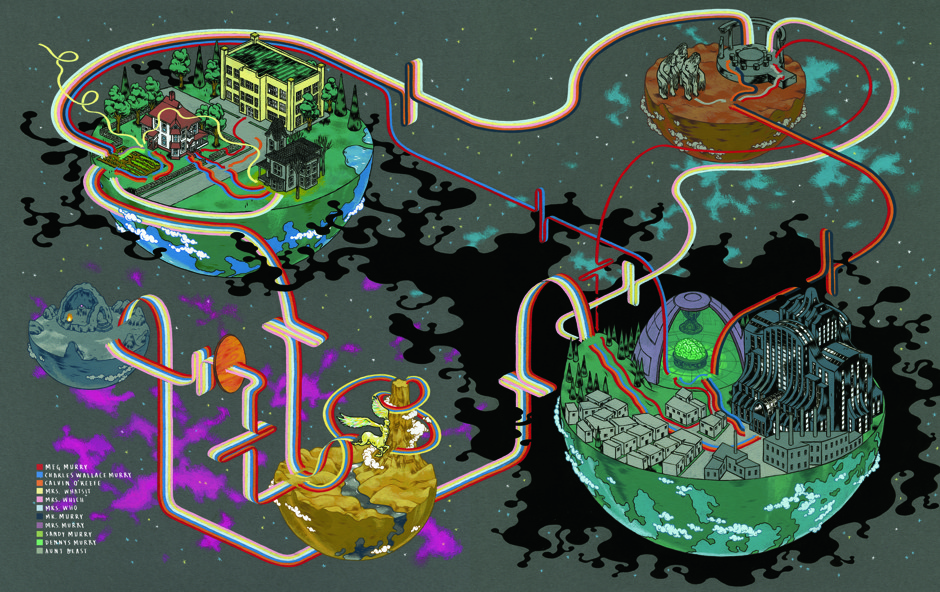

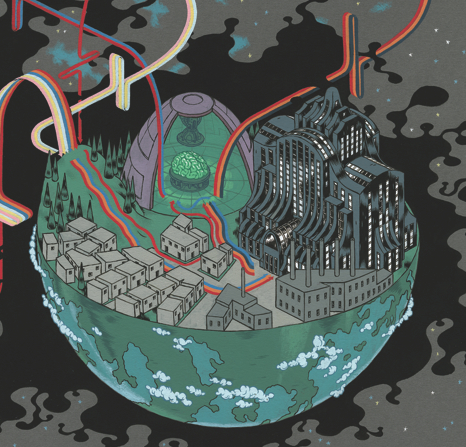

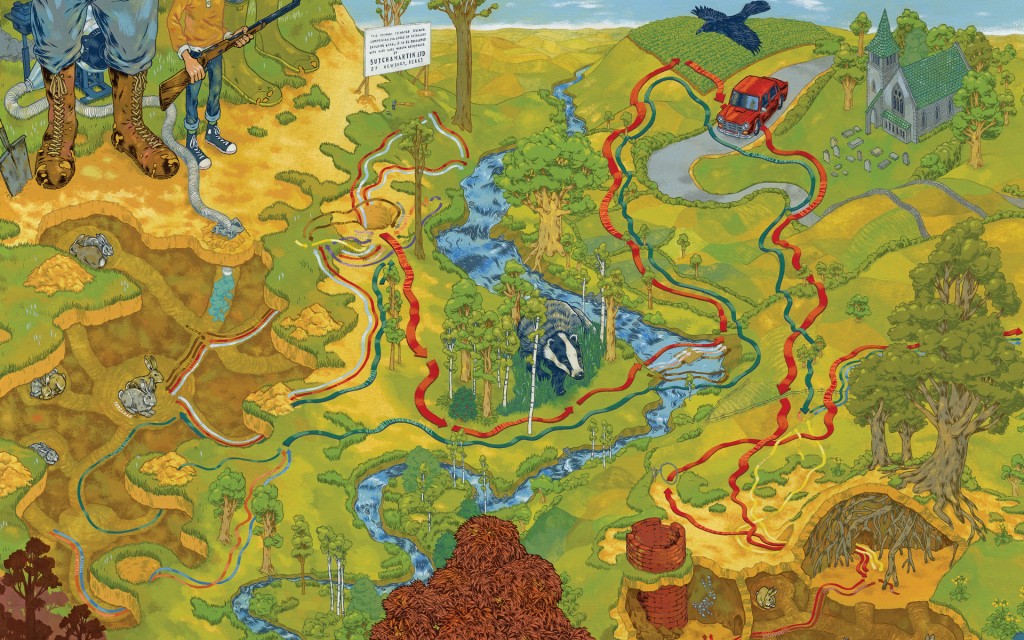

The Wrinkle in Time map is firmly set in the fantastical, and the visual universe that DeGraff creates is necessarily otherworldly, showing the Murray siblings’ journey through space with their witch guides. Brilliantly original painter and pop cartographer, Andrew DeGraff, uses his painting skill and cartographer’s ability to visualize multidimensional worlds, layering with aerial perspectives, proportions, and cut-away views, and a stunning amount of narrative and atmospheric information. For this particular book, you obviously can’t employ ordinary cartography, since the characters travel through space and time via a mysterious device called a tesseract. The tesseracts, then, are depicted as literal wrinkles in their journey lines. In addition to the lines that represent all the characters, the novel’s ominous antagonist, “The Black Thing,” is represented in black splotches on the map. The stunning map uses colored lines to represent each fictional character’s journey through the galaxy of the novel, with detailed illustrations of each of the planets they visit along the way.

100% hand-painted map of “A Wrinkle in Time” (All photos: Andrew DeGraff/Zest Books)

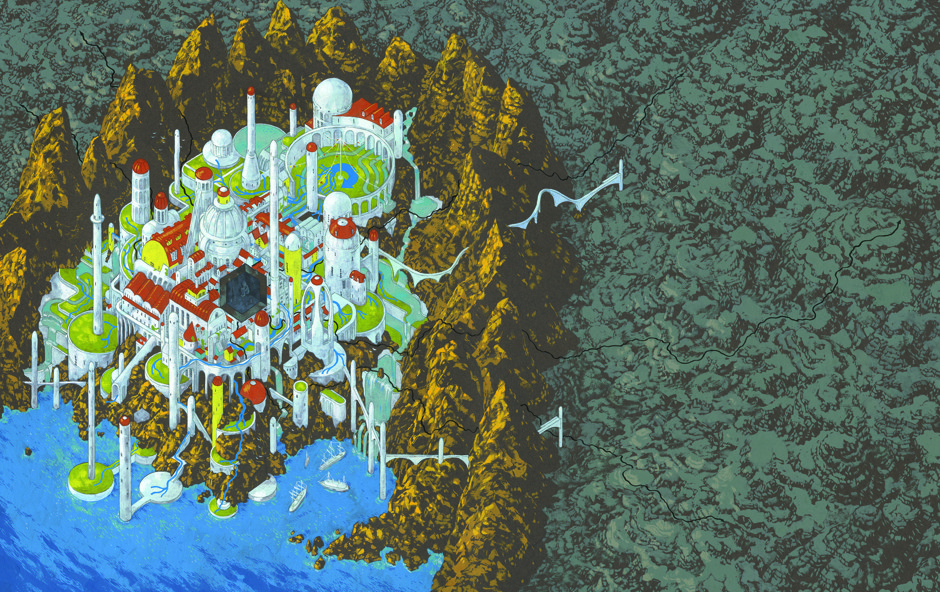

The planet of Camazotz, which is dominated by The Black Thing. (Andrew DeGraff/Courtesy of Zest Books

Besides a Wrinkle in Time, Plotted, offers incredibly detailed, cleverly structured geographies of 19 easily rendered classic books, including Hamlet, Pride and Prejudice, Invisible Man, Watership Down, A Christmas Carol, Huckleberry Finn. I like how each map features its own location-specific artwork and color scheme, individual to each book. Breathing new life into the dying art of cartography DeGraff’s intricate and vibrant illustration dish up a new perspective on stories we all know, while drawing us deeper into fictional realms.

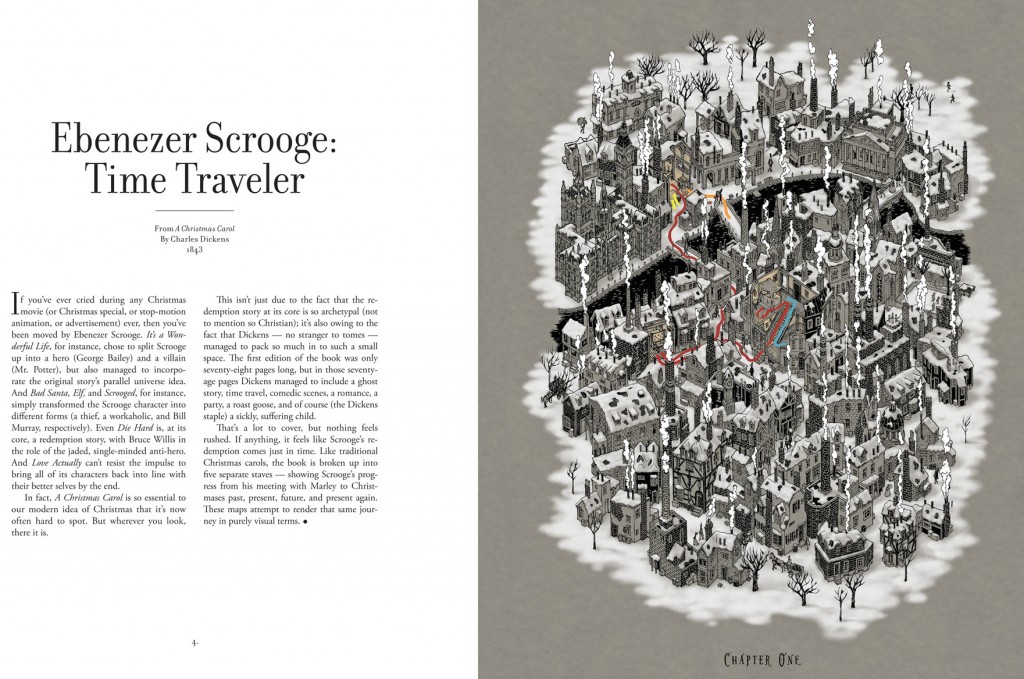

There is two-page spread to each of the five acts in Hamlet, using colored lines to trace the movements of the play’s characters. A similar approach is applied to A Christmas Carol through a series of maps that allow readers to follow Scrooge’s journey with each ghost. Pride and Prejudice is cleverly depicted through the eyes of Mrs. Bennet. Each family has a house, the heights of which are based on social standing, with Mr. Darcy and Mr. Bingley soaring to the top and the sleazy Mr. Wickham at the bottom. When the characters marry, as they are wont to do, they meet between their houses, connected by driveways. I loved the fact that the Bennet’s house has two doors left empty to represent the unmarried Mary and Kitty.

There is two-page spread to each of the five acts in Hamlet, using colored lines to trace the movements of the play’s characters. A similar approach is applied to A Christmas Carol through a series of maps that allow readers to follow Scrooge’s journey with each ghost. Pride and Prejudice is cleverly depicted through the eyes of Mrs. Bennet. Each family has a house, the heights of which are based on social standing, with Mr. Darcy and Mr. Bingley soaring to the top and the sleazy Mr. Wickham at the bottom. When the characters marry, as they are wont to do, they meet between their houses, connected by driveways. I loved the fact that the Bennet’s house has two doors left empty to represent the unmarried Mary and Kitty.

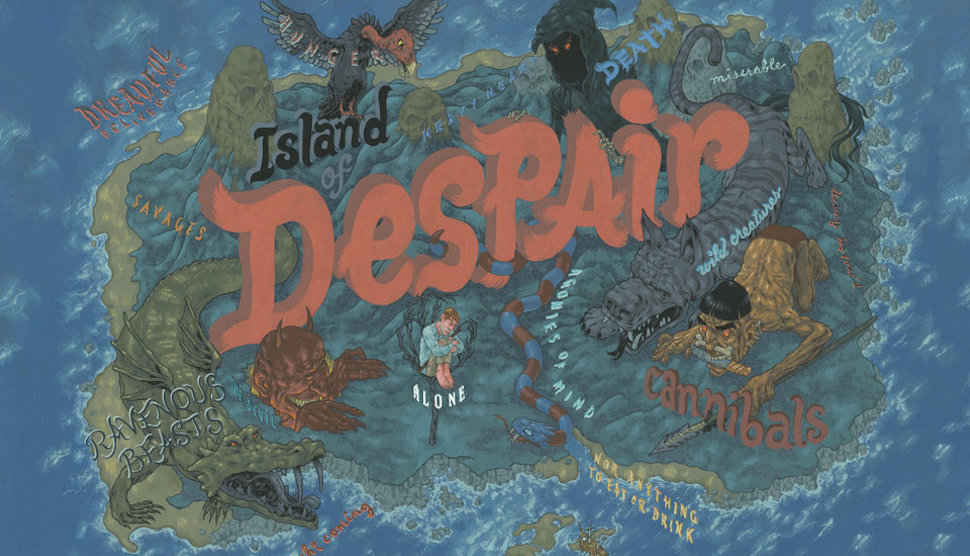

Robinson Crusoe by Robert Louis Stevenson (Andrew DeGraff/Courtesy of Zest Books)

In the case of Moby Dick, which has been imagined so many times, Degraff opts instead to map the ship on one page and the whale on the following. The map is a cross-section of the Pequod itself—and then a remarkably similar cross-section of a whale, its ribs and holds and rudders laid bare for the reader to investigate.

The map of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot is hilarious and accurate. Vladimir and Estragon are represented by two anthropomorphized speech bubbles with arrows signifying Pozzo and Lucky circling around them; the rest is a blackish orange, with suggestive white shapes on the other side, just popping into frame, to hint at the world going on just beyond these two hapless men.

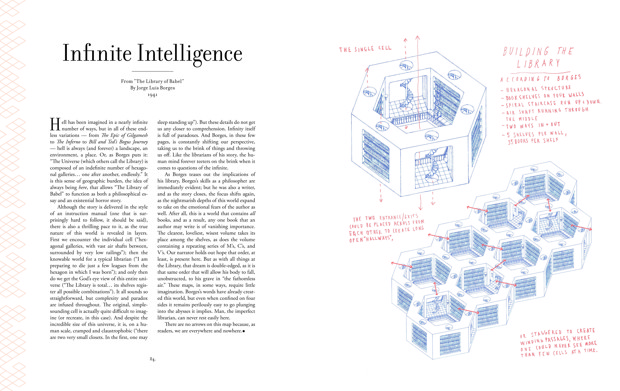

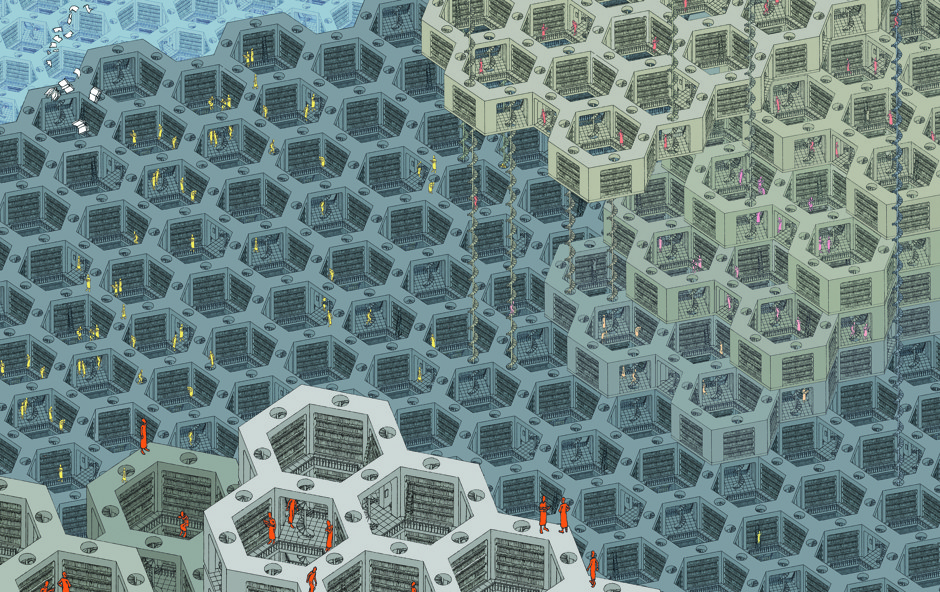

For the Jorge Luis Borges’s short story, “The Library of Babel,” the author imagines the universe as a series of adjacent hexagonal rooms, with neither characters nor a journey. It is an endless library comprised of “an indefinite, perhaps infinite, number of hexagonal galleries, with enormous ventilation shafts in the middle, encircled by very low railings. The Library contains all possible books ever written, and is so full of knowledge that it is actually quite useless to its patrons

DeGraff first presents a wide view of the Library from above, so it looks like a detail of a mechanical beehive. Then, in a close-up, we can spot people in the galleries, wandering around, looking for answers.

DeGraff first presents a wide view of the Library from above, so it looks like a detail of a mechanical beehive. Then, in a close-up, we can spot people in the galleries, wandering around, looking for answers.

“The Library of Babel” (Andrew DeGraff/Courtesy of Zest Books

“The Library of Babel” (Andrew DeGraff/Courtesy of Zest Books

This second map takes is Escher-like. “The Library of Babel,” like much of Borges’s fiction, lies just outside of human understanding, because humans can’t wrap their heads around the idea of infinity. DeGraff’s map captures that ineffable spirit, somehow, in that most rational of human inventions: a map.

Check out this video on the makings of his Robinson Crusoe map:

Watership Down by Richard AdamsThe Library of Babel” (Andrew DeGraff/Courtesy of Zest Books)

Watership Down by Richard AdamsThe Library of Babel” (Andrew DeGraff/Courtesy of Zest Books)

In DeGraff’s cartographical rendering of Around the World in Eighty Days, Jules Verne’s 1873 novel, we have a vivisection of a globe floats bowl-like in the air. The top layer compresses the numerous landmarks of Phileas Fogg’s adventure, from London on the first day to Bombay on the 18th to Salt Lake City on the 64th and back to the point of origin.

Around the World in 80 Days (Andrew DeGraff/Courtesy of Zest Books)

The bottom half of the divided globe is made up of steel beams and looks like an unfinished building, hinting at the fabricated, stage-managed nature of fiction itself. DeGraff notes that the real pleasure of Around the World in Eighty Days derives from Fogg’s “passionate chase of a technocratic dream,” and he’s right. But we also take pleasure in Verne’s dream, his elaborately designed and constructed fantasy, his invention of a world that seemed unbelievable until millions of people started living in it.

The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas” (Andrew DeGraff/Courtesy of Zest Books)

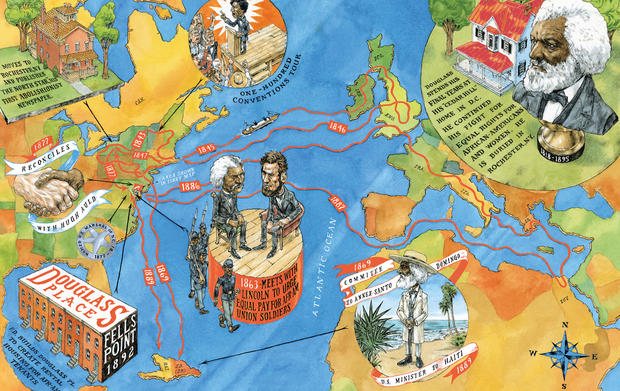

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglas, An American Slave, by Frederick Douglas (Andrew DeGraff/Courtesy of Zest Books)

The details from the intricate, six-page map of Huckleberry Finn illustrates in eye-opening fashion the artist DeGraff’s assertion that Huck, surrounded on all sides by “hucksters, racists, zealots, bloody-minded aristocrats, and simple-minded fools,” illuminates the book in his role as skeptic and arbitrator: “Always being grappled with by people on both sides, he stays in the middle. He defines his own morality, makes his own course, and continues on.”

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Andrew DeGraff/Courtesy of Zest Books)

Plotted is a colorful, elegant book and a thrillingly original approach to illustration. It also shells out some interesting insights about our inner perceptions of fiction, and the ways in which we tenuously hold fictional universes in our heads. Are we influenced more by our interpretations of the text than by what the author actually tells us is there? What parts of a novel do we see, and what parts do we only think we see? In literature, as in life, we can’t see everything, or keep track of all the details or truly envision specific geographies, even ones we’ve visited lots of times before.

I love maps. There’s something about cartography that lends itself to visualizing much more than land and geography. Maybe it’s the unmovable order of things on a map, the putting everything precisely where it is supposed to be. In the sketchy and ever changing INFORMATION AGE, absent anything concretely visual to latch onto, we create messy, complicated maps to maintain a grip on the disorienting profusion of stuff thundering towards us. The visual display of quantitative information is something I can understand and doesn’t freak me out. Writers love maps. Literary cartography being literal maps as well as the geographies they describe. A map not only gave Robert Louis Stevenson a setting for Treasure Island; it shaped the novel’s narrative and characters. Stevenson wrote that, when he “pored upon [his] map of ‘Treasure Island,’ the future characters of the book began to appear there visibly among imaginary woods; and their brown faces and bright weapons peeped out upon me from unexpected quarters, as they passed to and fro, fighting, and hunting treasure, on these few square inches of a flat projection.” The map printed in the novel’s pages was not some final flourish but a record of its very origins. Maps describe places where people have already been in order to show everyone else how to get there. Fiction is made of maps to places no one has ever seen, and when we all arrive at our destinations, none of us end up in the same place.

If we could transcribe a mental representation of my brain, it would probably look less like DeGraff’s thorough, well-executed images and more like those medieval maps, with small pockets of knowledge surrounded by huge swaths of emptiness.

Plotted was released under Zest Books’ Pulp imprint, which was started in the fall of 2014. Zest Books often releases titles that run the line between adult and YA.

Product details: Hardcover: 128 pages

Publisher: Pulp; Original edition (October, 2015)

Language: English

ISBN-13: 978-1-936976-86-7

Andrew DeGraff attended Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and also teaches there and lives in San Francisco. Daniel Harmon is a former staff writer for Brokelyn.com.

Images via Atlas Obscura’s Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history.

buying information @ Zest Books