Ebola, global warming, heat death, yadayadayada, it seems as if even day a new type of medical or environmental horror is attacking us from the headlines. The Vallows are sciencey people, engineers, doctors and research scientists and me, a cartoonist who likes to read about stuff, particularly if there is an element of MYSTERY afoot. Germs and detectives might not seem like they’re connected. But their link, as a certain fictitious sleuth might say, is elementary. Here are some books I have read recently that you may ALSO enjoy!

Spitting Blood: The History of Tuberculosis by Helen Bynum

Spitting Blood: The History of Tuberculosis by Helen Bynum

I have always been fascinated by the romantic “wasting” disease. It started as a kid when I read the story of Poe’s child bride’s death by consumption. She is entertaining guests in the parlor on the harp (or was it a piano?), and suddenly starts spitting up blood. She spends the next months growing paler and more wan and more beautiful, glowing with the disease. During the Romantic Age, TB was called “consumption,” from the Latin, consumere, to waste away and for a brief period, became a stylish mark of tragic beauty. The pale and wan English poets, like Keats and Shelley, symbolized the melancholy ideal of the romantic and consumptive youth of the 19th century, such as Mimi, in Puccini’s La Bohème. Romantics began to believe consumption was associated with gifted and talented people; Thoreau, dead at 45; Chopin, 39; and Robert Louis Stevenson, 34. It was the professional and popular opinion then, before the discovery of germs, that consumption was a constitutional trait.

Reading Spitting Blood, it is difficult to accept the atrocious toll this ancient disease still takes on human life, despite several centuries of concerted scientific effort. Bynum castigates the “casual disregard” we have shown this deadly condition. Each year, almost 9 million new TB infections take place and some 1.4 million deaths. George Orwell’s’ battle with pulmonary tuberculosis ended when he “drowned in his own blood” after a severe lung hemorrhage in 1950, aged 46. Tuberculosis kills the young, and the disease is an important reason why many nations remain mired in poverty.

Perhaps the major conclusion of Bynum’s investigation is that TB is not simply an infectious disease – it is a social disease. It attacks the poor, the underprivileged and the vulnerable. There really isn’t anything romantic about it at all.

Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic by David Quammen

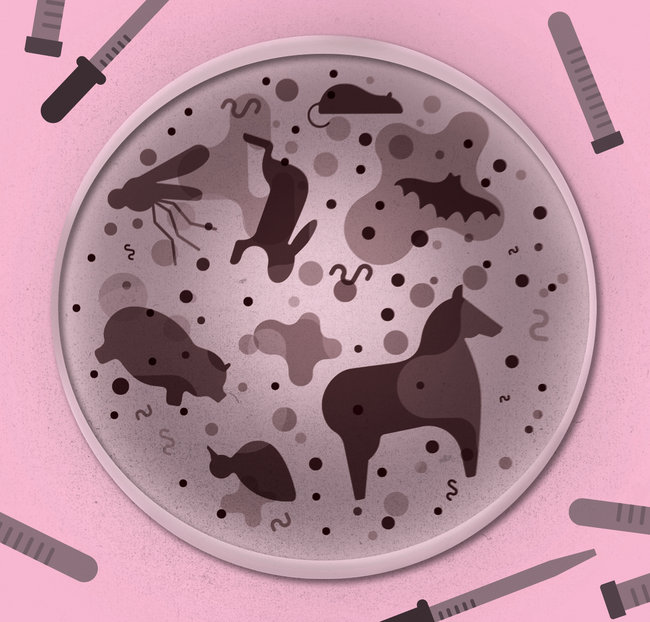

A Sprawling detective story with a vast host of murderers; viruses, bacteria and single-celled organisms which infect other animals, but every so often make the jump – spill over – to us humans. Each chapter follows the quest to track down a new villain. An international team of hero detectives – scientists – slave away in the field and in labs, uncovering the traces which will lead them to the killers (too often the BAT), often getting jabbed with infected needles themselves.

An opening chapter almost had me put Spillover away: about a horrific virus that was particularly upsetting to me, which lays waste to horses (and humans), eventually leading us to fckng FLYING FOXES aka GIANT FCKNG BATS. The Ebola virus emerges through a grim tale with piles of dead apes in the forest, consumption of rotting bushmeat, sorcery and Rosicrucianism. Quammen doesn’t sensationalize this stuff because he doesn’t need to, it is horrific enough. He promises to tell us the “complicated story”, not the dramatic one. Quammen wants you to understand and wants you to be invested. His writing style is morbidly entertaining and doesn’t mind repeating himself (he admits it outright, repeatedly). Still, a consummate piece of science writing that you’re likely to imbibe some extremely complex concepts without realizing it.

Quammen writes: “We are “tearing ecosystems apart,” and animals and humans are rubbing shoulders in novel, unexpected ways. The steady drip of animal microbes spilling over into people quickens. less public health warning than ecological affirmation: these crossovers force us to uphold. People and gorillas, horses and duikers and pigs, monkeys and chimps and bats and viruses,” Quammen writes. “We’re all in this together.” Stop taking antibiotics for viruses and get your flu shots, folks! And remember: “The duck is the Trojan horse.”

Advice For a Young Investigator by Santiago Ramon Y Cajal, Neely Swanson and Larry W. Swanson

Advice For a Young Investigator by Santiago Ramon Y Cajal, Neely Swanson and Larry W. Swanson

Santiago Ramon y Cajal was a mythic figure in science, hailed as the father of modern anatomy and neurobiology, and largely responsible for the modern conception of the HUMAN BRAIN. Before Cajal, the scientific community viewed the nervous system as a continuous strand. Cajal argued that any attempt to operate on one part of the brain would disable the rest of it, like pulling out a bulb from those old-fashioned kinds of strands of Christmas tree lights. Cajal laid the foundation for much of what we now know about how the brain works.

Cajal talks about science as a superior form of human evaluation and the limitations of subjective reasoning, and provides insights into his unconventional investigative process.

The Logic of Scientific Discovery by Karl Popper (German: Logik der Forschung,which, literally means “The Logic of Research”).

The Logic of Scientific Discovery by Karl Popper (German: Logik der Forschung,which, literally means “The Logic of Research”).

Popper argues that science should adopt a methodology based on falsifiability, because no number of experiments can ever prove a theory, but a single experiment can contradict one. Popper holds that empirical theories are characterized by falsifiability. This book revolutionized contemporary thinking on science and knowledge. Ideas such as the now legendary doctrine of ‘falsificationism’ electrified the scientific community, influencing even working scientists, as well as post-war philosophy. Popper has a straightforward, lucid writing style, as a book on epistemology needs to be easy to read and understandable.

“The Remedy: Robert Koch, Arthur Conan Doyle and the Quest to Cure Tuberculosis”

“The Remedy: Robert Koch, Arthur Conan Doyle and the Quest to Cure Tuberculosis”

A real-life medical detective story highlighting a pair of unlikely heroes who crossed paths in Berlin in 1890 and forever changed the landscapes of medicine and literature.

Before Robert Koch discovered the cause of tuberculosis, he was a provincial German physician (think CHARLES BOVARY), with the dream of becoming a famous scientist.

Before Arthur Conan Doyle got rich with Sherlock Holmes, he was a small-town English physician with dreams of becoming a famous writer. The idea of scientific detective work inspired Doyle to give up medicine and pursue literature full-time, and Sherlock Holmes—with his signature “science of deduction” technique—was born.

Their two narratives are weaved through a history of medical best practices, a period marked by improved hygienic practices and the possibility of new vaccines. It’s a page turner, that takes place in the final decades of the 19th century when tuberculosis was an incurable scourge that killed indiscriminately and ravaged populations; for decades, it was the leading cause of death in Europe and the United States. The origin of the disease was a complete mystery, as was its uncanny ability to travel from one person to another. The age of electricity was dawning. And in laboratories and on imaginary London streets, men armed with microscopes and the power of observation first used science to tackle the twin scourges of crime and disease.

Genius on the Edge: the bizarre double life of r. William Stewart Halstead by Gerald Imber

Born in New York City the same year as Cajal, William Stewart Halsted didn’t decide to study medicine until he was a senior at Yale, a choice that profoundly affected the surgical field. The book very realistically portrays the agony of operations a century ago when the mortality rate was as high as 99 percent. Today it’s 1 percent, in part because of Halsted, whose genius often came from common sense like washing your fckng hands and wearing scrubs.

There are so many salacious and entertaining bits in Halstead’s life that makes this a real page turner. There is the implied possibly that he is gay, the whole Jekyll and Hyde part of his personality thing, his drug addictions and his mysterious, unexplained disappearances. The gay thing is barely substantiated, mostly stuff like his marriage at age 40 to a plain woman who wore masculine clothing and that she and Halsted had separate bedrooms. His obsession with improving anesthesia led to self-experimentation which led to a cocaine dependence. The Jekyll and Hyde simile is quite salacious. In the hospital, with nurses, staff and co-workers, Halsted was stiff, painfully shy, reclusive, unapproachable, severe, sarcastic, sometimes cruel. But with his close friends, at his club after his afternoon drugs, his charm and humor shine through. His cocaine habit was “cured” with a lasting heroin addiction. Despite this, Halsted never lost his humor, famously observing: “Surgery would be delightful if you did not have to operate.”

Harvey Cushing: A Life in Surgery by Michael Bliss

Without the influence of Cajal and Halsted, the career of Harvey Cushing, one of America’s first neurosurgeons, might not have been possible. And without Cushing, many modern careers would not exist. In this biography, Michael Bliss describes a genius with relentless ambition, a mentor and tormentor, a perfectionist who often forgot the line between confidence and arrogance.

Bliss details Cushing’s obsession with improving all aspects of surgical care, as well as clinical diagnostic methods. Dr. Cushing was performing brain surgery during the earliest days of brain surgery, when doctors had no imaging tools to locate a tumor or proper lighting to illuminate the surgical field; when everyone was filthy, when anesthesia was rudimentary and sometimes not used at all; when antibiotics did not exist to fend off potential infections. Some patients survived the procedure — more often if Dr. Cushing was by their side. Dr. Cushing also discovered that pituitary tumors could lead to vast changes in the body. Cushing’s disease and Cushing’s syndrome — two illnesses linked to hormones gone awry — are named for his discoveries.

Dr. Cushing collected cancerous brains which were later donated to Yale on his death in 1939 — along with meticulous medical records, before-and-after photographs of patients, and anatomical illustrations. (Dr. Cushing was also an accomplished artist.)