I am both proud and ashamed to admit that I have an entire room dedicated to the annals of teen detective fiction. I own and have read not only every Nancy Drew mystery multiple times, but all the other teen detectives, too: Trixie Belden, Judy Bolton, Beverly Gray, even the Hardy Boys. Basically, I am very familiar with the entire canon of teenage sleuthery.

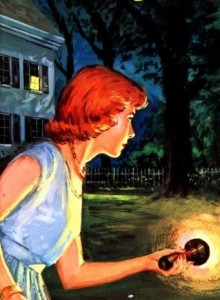

But it was seminal teenage detective Nancy Drew who was the first, the original. She was the one. Lithe, blue eyed, titian-tressed, teen dream Nancy, the girl goddess from whose golden egg all other girl sleuths were hatched. Nancy was born on May 1st, 1930 – the octogenarian teenager celebrated her 80th birthday this month – making her the oldest living teenage sleuth still active in the business of solving mysteries. Nancy Drew was the brainchild of a sinister sounding “novel factory” called Stratemeyer Syndicate. “The Syndicate” sausage factory’s stable of ghostwriters were already cranking out boy’s serial fiction such as The Hardy Boys and The Rover Boys as well as the creepy Bobbsey Twins and the even creepier Honey Bunch series. It was the “golden age” of noir detective fiction and from The Syndicate’s diabolical ingenuity sprung a unique book commodity: popular old-fashioned adventure stories infused with spicy modern crime, packaged for teens. Nancy was The Syndicate’s IT Girl, a slim and stylish embodiment of the era’s “New Woman” who worked, voted and lived her life independent of men. She was an instant smash, selling like Hannah Gruen’s hotcakes in the nadir of The Great Depression. As the book’s popularity grew, new ones were churned out year after year, and Nancy was tailored to fit each successive era. In terms of popularity, Stratemeyer Syndicate was the Stephanie Meyer of it’s day. But with writers.

As you should already know, Nancy is a 16 year old amateur sleuth whose home base is a large, red brick house at the end of a path of her own prized blue larkspurs, in a sunshiney anywhere town called River Heights. Her mother is dead but no matter! The Drew’s housekeeper Hannah provides the motherly comfort without actual interference as well as the onslaught of delicious meals. Nancy’s father, a “world famous” attorney, is equally non interfering with the added benefit of being wealthy. Nancy is as cool as a zesty orange ice, completely unfettered by life, enviably self-possessed, with a double dose of moxie.

Nancy Drew ghost writer and Wellesley college alum Harriet Adams said that Nancy was modeled after the Wellesley motto Non ministrati sed ministrare (to minister, not be ministered to).

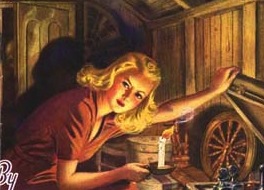

Nancy is an autodidactical freak of nature, talented and focused to the point of pathology: She has a mind like a steel trap and – despite never spending a day in a classroom – is adept at handwriting analysis and archaeology, familiar with avian anatomy, is multi lingual and learned in psychology. She is masterful at using the powers of suggestion and judging a person’s character based solely on appearance, “although she had heard the man was a very good player, she had taken an instant dislike to him, and politely declined the invitation”. She is alert and observant, noting misplaced objects, torn hems, license plate numbers at a distance, a fake telephone from across the room. She recognizes an Electric Fence of Death when she sees one. She is a near expert in discerning dialects and vocal qualities and subtle changes in behavior. Even in moments of deepest peril, Nancy stays cool and is able to excogitate an escape by dropping clues, like a dress pin or a button, forging maps and sending carefully encoded messages.

Nancy’s wealth of talents is mind-boggling. She is a fine painter, a skilled boatsman and driver, paralleling into the tightest parking spots and turning breakneck u turns. She is capable of fixing her car and moving trees or boulders out of the car’s path. She can pilot and drain fuel from planes, fix a boat’s motor with a bobby pin, restore a damaged painting with precision, whip up a couture gown, speak fluently in French, forge any handwriting, read Chaucer in Olde English, is very familiar with nautical terms and is able to interpret a Shakespeare sonnet or a Chopin etude with nuanced understanding and – with the advantage of both a photographic memory and an artist’s subtle touch – can expertly render a criminal’s likeness for the police.

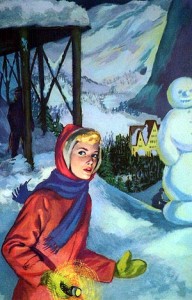

Nancy is no tomboy, God no. But she is athletic and agile and plays a mean round of tennis and golf. She is a skilled marksman, fencer and oarsman, swims like a fish, dives like a swan and is excellent at water ballet. Nancy is adept at ocean fishing, skin diving and bobsledding. She can play the bagpipes and is a ping-pong champ. She rides like an equestrian, English, Western and “trick.” Nancy is a self starter who easily learns underwater photography and auto mechanics. When called upon, Nancy is able to perform as a circus stunt rider and when a wintertime mystery presents itself, Nancy is a natural-born skier and – this is the real kicker – unbeknowest to us, was once a top notch, trained figure skater, and she steps effortlessly into a fluffy white skating skirt and onto the ice for an impromptu pairs programs.

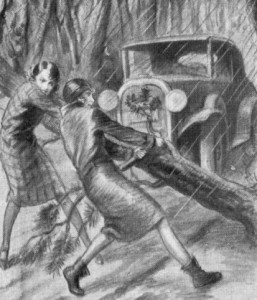

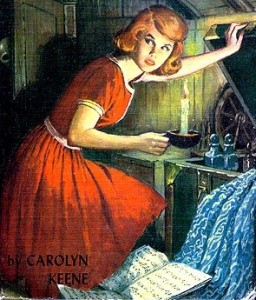

Nancy speaks many languages (but not Greek). She bakes like Betty Crocker and dances like Ginger Rogers. She is able to improvise a ballet and tap dance like Shirley Temple…but in Morse code. She can soothe a terrified child and administer first aid like Florence Nightingale. She chases villains over snowy fields, through wooded glens, down Scottish cliffs and into dark alleys. She doesn’t need fancy gadgets – when she finds herself trapped in a closet, cistern, chimney, cave, cellar, library, boat, tower or tack room, she is as resourceful as MacGyver, escaping using coat hangers, tapping sos in morse code, using bobbie pins, handkerchiefs and hair combs, as whatever, a rain slicker to stop up a hole in a flooding canoe, a flashlight to blink SOS in the middle of a blinding snowstorm (on snowshoes, naturalment).

Nancy’s raison d’etre is righting life’s wrongs, allaying fears, reuniting lost love ones, exposing greed and graft, sniffing out imposters, restoring treasures to their rightful owners and bringing villains to justice. Nancy is a shining beacon of justice and charity, helping the helpless and the hapless, championing lonely old ladies and the poor, standing up for bilked heiresses, down-on- their-heels spinsters, orphans and indigents, aristocrats and princesses. Nancy Drew regularly engages in questionable, often illegal behavior to get to the truth: breaking and entering; running red lights; speeding through the quiet streets of River Heights; trespassing; picking locks; swiping evidence; snooping in police files; impersonating an elderly maid by dusting her hair with talc then rummaging through the suspects personal stuff; borrowing identities and jimmying locks. All with the grace and aplomb of Grace Kelly, and no repercussions. Somehow she operates within society even while transcending its limitations and breaking it’s rules.

Nancy is slender, graceful, immaculate. She is “attractive,” but not “beautiful.” Of course, she is beautiful, but Nancy is modest and serious about her work, shrinking from newsies snapping her photo after performing heroics on an out of control ferris wheel. She never worries about her looks like Bess, but is the one to always turn every head in every room. Nancy’s lack of concern over her attractiveness to the opposite sex keeps a steady stream of admirers heading her way. In The Secret of Red Gate Farm we are told: “Nancy did not like to be told that she was pretty. She preferred to be called interesting”. She likes her clothes, to be sure and looks good in everything. She is always fashionable but never flashy. When she is offered a pretty bejeweled hair clip in The Clue in the Jewel Box Nancy demures: “Mrs Gruen never wanted me to wear fancy jewelry”. Her hair isn’t red it’s titian, her eyes are “sparkling sapphire blue” and her heart-shaped face is fair, except for when she is praised and her cheeks blush like apples.

Nancy’s father is rich, tall, dark and handsome, yet has zero social life and his hobbies are bowling and growing roses. Without his spectacular daughter to live vicariously through, he is kind of a dud, like all the men in Nancy’s world. Nancy never has to whine about curfew, car keys or permission to run off for the weekend unchaperoned. In The Clue of the Broken Locket: “Mr. Drew realized it was best not to argue with Nancy when she had a particular goal in mind, even if his own instincts advised caution” and nancy chimes in: “You’re a peach, Father. You let me do anything I like”. Nancy not only has his absolute trust, Mr. Drew allows her to engage in risky behavior and eggs her on with “case information”. Carson Drew’s deep pockets allows his daughter to remain an “amateur,” and his own sorry, dateless widower’s life ensures that Nancy will always be his #1 girl.

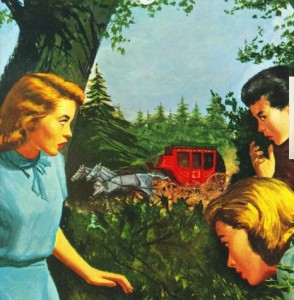

Crucial to Nancy’s career is her ability to travel freely about the country, which she can do thanks to a swell birthday gift from Dad: a sweet blue roadster with rumble seats. She and her chums race around River Heights at high speeds, after dark and with no seat belts. When her beloved roadster is stolen, threatening her departure time to New Orleans with the girls, Mr. Drew literally dashes out and returns with a brand new car, a better car, a sunny yellow convertible. You might expect a pang of regret over the loss of her trusty roadster but there is no time for sentimentality in Nancy Drew’s world, there is a mystery brewing in The Big Easy! Besides, as Bess points out about the old car: “There was an ink stain on the seat anyway”. And the chums race off in the new car, never looking back.

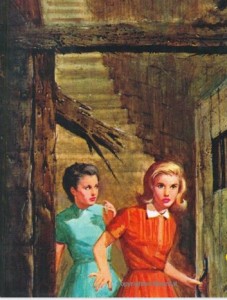

The absence of a mother to impose restrictive feminine stereotypes on her – like marriage, housework or applications to Smith or Bryn Mawr College – is a serious advantage for a girl detective. Any mother whose 16 year old daughter was regularly being kidnapped, chlorophormed, poisoned, bound and gagged, tied to the hull of a ship, attacked by wildcats, choked, crushed in an avalanche or landslide, tied up aboard a sinking ship, bonked on the head with the butt of a gun and dragged to a basement and left to starve – or drown – would have called the whole thing off. In the absence of bourgeoise money concerns, consequences or a mother’s nagging (“go to school”, “don’t drive 90 mph over that rickety bridge and break into that old house”), Nancy is free to race out in a storm at midnight with a revolver, illegally break into a spooky mansion and fall through the floor (in The Hidden Staircase). Nancy herself, of course, always comes off as nearly infallible. Any concerns over her own safety or doubts about her own capablities are fleeting, and she takes setbacks in stride. Nancy doesn’t just defy conventions, she poo-poos them, revs her engine, waves and speeds away. It never occurs to her that dangerous detective work might be an unsuitable job for a teenaged girl.

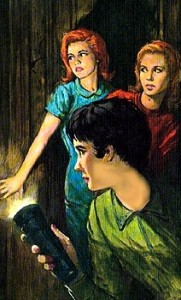

Through Nancy Drew I discovered the glorious concept of “chums” (possibly the only time this word is used as anything other than fish bait). I learned that chums could do anything but anything was done best with BFFs in the rumble seat of a spiffy sports car, with an emergency overnight bag and well-stocked picnic basket in the trunk. Cousins George Fayne and Bess Marvin are as different as those Patty Duke cousins. George is a tomboy, bold, athletic, boyishly slim with short black hair and a turned up nose. She is a judo champ and favors tailored clothes and no jewelry. She is “indifferent to boys“. Pretty Bess is emotional and compassionate, insecure and self-effacing. Often careless, Bess endangers the chums when she accidently buys a bottle of poisonous perfume at the Mon Coeur cosmetics counter. She is described as “plump” but looks perfectly slim. She is often mocked for being hungry and has said “I don’t know which is harder: to keep on a diet or keep in a secret!” Once, “they all drained their glasses of fruit punch, Bess looking wistfully at the maraschino cherry which obstinately remained in the bottom of her glass”. Together, the chums juggle intense crime solving adventure with girlish delights, like shopping, dressing up, picnicing, boating, baking and eating (much) more on the eating later.

Every Nancy Drew story is a hybrid of pure mystery and fantastical adolescent fantasy. The stories gallop along, there’s simply no time to waste as the sleuth saves lives, cracks cryptic codes, pursues suspects, chases down stolen goods, stops for a 4 course lunch, picks locks and pilots planes. Nancy is on the go. Even when she drives, she speeds. The successful teen detective lives in a world without sentimentalizing, psychology or self-reflection. Off they go, to wherever the next mystery is breaking.

The breakneck speed of the prose and the dearth of atmospheric detail leaves the pre teen girl reader salivating for the slivers of tantalizing description – namely tchotkes, outfits, locations and food – which reads like porn: “an oriental rug with secret code woven into it’s decorative border” or: “French crystal earrings in the shape of larkspurs; “And in a mysterious curio shop: “In the back of the case, under glass, were several locks of hair held in place with tiny clasps set with rubies”. There is an unending supply of titillating places, treasures, objects and clues for the pre teen bookworm;

“A Pink enamel easter egg on a tiny gold pedestal with a rounded cover encrusted with delicate gold work opens to reveal a tiny tree made of emeralds, and a nightingale on its branch.”An ivory elephant charm, old clocks; broken lockets; missing treasure; falling chandeliers; pirate booty; smuggled jewels; stolen cameos, moonstones, spider sapphires and emerald rings; twisted candles; mysterious miniatures; brass-bound trunks; jewel boxes; missing maps, wills and letters; important documents written in invisible ink; bisque figurines; leather bound diaries tied in ribbon; tampered-with oil paintings; an oriental vase emblazoned with graceful orchids; poisoned perfume; imposter princes; stolen ballet slippers; an angora kitten named Snowball; a bejeweled, monogrammed bottle of smelling salts….

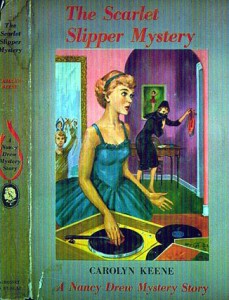

In one of my favorite of the series weighty tomes, The Mystery of the Scarlet Slippers, Nancy discovers rare jewels imbedded in the paint of a fine oil portrait of a world renowned ballerina, in the tulle of a diaphanous pink and white tutu and in the toes of the satin, scarlet slippers themselves. It’s almost too much.

“The Syndicate” was clever enough to employ two very important literary devices in their series. One is never ending the books before the reader is offered a tantalizing glimpse into the next mystery. Otherwise, 10 year olds have to walk around with that day after Christmas feeling. At the end of The Mysterious Letter, after the exciting mystery has been solved and Nancy is headed back to River Heights, we learn that “the young detective always felt a vacuum in her life when this happened.” It’s the same feeling I felt after every birthday or pony show. Another time-worn device is matter-of-factly killing off one or both of the parents. This adds mystery and gravitas to our heroes and lets them roam free, testing their boundaries, breaking the rules (and the law), and have wildly dangerous adventures without parents – especially mothers – hanging around.

Virginal and unromantic, Nancy is unconcerned with matters of the heart and steadfastly refuses to let the opposite sex interfere in her life. She has a technical boyfriend (only so we know that amongst the chums at least Nancy isn’t gay), whom she never kisses and whom she refers to as her “special friend”. Collegiate Ned Nickerson is as harmless as a kitten, as sexy as a chair. He is always handy to escort Nancy to the carnival or to exclaim, “what a doll!” as she appears in a new frock. Ned is called on to help but is never her hero. He’s the “good egg”, straight as an arrow, conveniently absent when not needed and never on Nancy’s mind. She cares more about the plight of the winsome orphan or the swindled old lady than any boy. “You may find yourself being called upon to do all kinds of outlandish sleuthing jobs,” she warns him, to which he replies, “I’m at your service.” Later, when called upon, he responds “At your service.” He is like the “formal dance guy” card in the Mystery Date Game – you know, the guy with the white tux, holding a corsage? Tall, clean – better than the slob or the ski bum, but not exactly “mystery date” either. A piece of cardboard.

Nancy has an aunt, the fabulous Eloise Drew, or “Aunt Lo” – a glamorous New Yorker, actually just a schoolteacher but with a Manhattan apartment. She is available to hostess or chaperone Nancy’s New York adventures and fixes elaborately mystery themed meals and takes the girls on big city shopping sprees where they stock up on hats, dresses, coats, stockings, bags, and of course vials of exotic “Blue Jade perfume”…..

Nancy’s villains are a colorful, cartoonish lineup of burglars, bunglers, blackmailers, kidnappers and catnappers, jewel thieves and pearl worshippers, horse thieves, imposters, bad bosses, evil foster parents, embezzlers, art thieves, bank robbers, mysterious scientists, thugs, smugglers, lowlife landlords and villainous rogues with names like Foxy Felix, Stumpy Dowd, Slippery One Caputti, Rudy Raspin, Snorky and Bushy Trot. They are usually swarthy, swaggering and greasy “He had slick, patent leather hair,” and Nancy can sniff them out a mile away. If their shifty eyes aren’t a dead giveaway than their sallow skin, raspy voice, thin lips, balding pates, or heavy breathing, are. Or their loud – often plaid – out of style, ill-fitting suits. They drive crappy cars with broken headlights and license plates. Nancy’s villains are rarely women, but colorful ladies often act as criminal’s molls. These hussies often have red – but not titian – hair, wear cheap perfume and too much makeup, have terrible taste in clothes and are pushy, rude and vulgar. “She was dressed in a flowered red and white dress, and a red hat was perched on her helter-skelter reddish hair”. One of these gals, the terrible Mrs. Judson – “an overdressed red-haired woman in her 40’s “with a “glittering, artificial smile” – – attempting to retrieve jewels hidden in the oil paint of a fine portrait – attacks Nancy with an artists’ pallette knife. Nancy sometimes exhibits her blue bloodiness, self importantly taking pity on these lowlifes, who usually hail from River Height’s parodic “wrong side of the tracks” and live in “rooming houses”. In the her very first adventure in Secret of the Old Clock Nancy immediately declares that the “Tophams”, a noveau riche River Heights family whose daughters Nancy know to be spoiled brats, don’t deserve the Josiah Crowley inheritance, despite their being named as sole benefactors in his will. Nancy decides that it is up to her to right the injustice of the Topham inheritance. Nonetheless, Nancy is motivated by unbounded empathy and and a sense of service to others, all the while belonging to the tony River Heights Country Club and active in charity work… like flower shows. Nancy’s blue larkspurs, of course, win first prize.

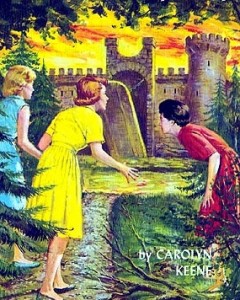

Nancy’s physical world is a theme park of spooky haunts; gloomy and decaying mansions; manor houses with attics and turrets; dude ranches (a dude ranch is practically a teen sleuth’s home away from home); summer cottages and lake houses; mysterious bookshops; New Orleans mansions; spooky ski lodges, Inns and hotels; and  historic castles. They have spicy names like the seedy Bon Ton Nightclub; Blackstone Hall; the haunted Lilac Inn; Red Gate Farm; Camp Merriweather; Pretty Face Cosmetics; Cedar Lake; The Rare Volume Bookshop; The Blue Iris Inn; Ship Cottage; Shadow Ranch; The Royale Creole; Deer Mountain Hotel and a town called Tartanville. Nancy lives in a world where there are still department stores (“Burkes”) with tea rooms (“The Golden Swan”), where she enjoys ladies luncheons (a term I use to this day) with the girls, usually a chicken salad sandwich and iced tea (what my mom ordered at “The Birdcage Tea Room” at “Lord and Taylors”). Like me, Nancy favors bookstores, antique and curiosity shops and does not like “imitations” only originals.

historic castles. They have spicy names like the seedy Bon Ton Nightclub; Blackstone Hall; the haunted Lilac Inn; Red Gate Farm; Camp Merriweather; Pretty Face Cosmetics; Cedar Lake; The Rare Volume Bookshop; The Blue Iris Inn; Ship Cottage; Shadow Ranch; The Royale Creole; Deer Mountain Hotel and a town called Tartanville. Nancy lives in a world where there are still department stores (“Burkes”) with tea rooms (“The Golden Swan”), where she enjoys ladies luncheons (a term I use to this day) with the girls, usually a chicken salad sandwich and iced tea (what my mom ordered at “The Birdcage Tea Room” at “Lord and Taylors”). Like me, Nancy favors bookstores, antique and curiosity shops and does not like “imitations” only originals.

Nancy is a clotheshorse, who, unlike me as a girl with my olive drab Danskin slimcut pants and a “Spirit of ’76” t-shirt, has a movie star’s closet. Snappy wool suits with matching accessories; sheathes, party dresses and dancing-frocks; pencil skirts; boat neck A-line dresses; pumps and penny loafers; kid gloves, clutch bags, cloche hats and belts; a “dainty ice blue blouse”; a “yellow evening dress spun of spider silk”; 3 quarter length, tailored dresses; flowered crepe gowns; red or yellow rain slickers. In The Secret of Shadow Ranch, Nancy buys herself a turquoise Indian costume with silver rickrack trimming to wear to the ranch barbeque. In The Bungalow Mystery, Nancy decides to stay overnight at a hotel for some late-night investigating and we learn that she always carries an overnight case in the trunk of her car: 2 changes of clothes, pajamas and robe, “toilet articles”, “swim togs” and “walking shoes”. And she always packs a cashmere cardigan with pearl buttons in case it got cold. She was always prepared to check into an Inn for the night. The chums all obsess over outfits, to the point of distraction. When their steamer trunk carrying their outfits is lost, it is treated as a pretty serious problem: “We have nothing to wear!”

Nancy can change her sensible detecting clothes for an evening dinner party or dance. She “floated downstairs in a sheer yellow, formal with gold accessories.” For a fraternity dinner dance, Nancy wears a pale green chiffon dress and gold evening shoes. For a masquerade ball in The Clue of the Velvet Mask, Nancy is meticulously costumed as a Spanish Senorita in a “red gown with a long sweeping skirt and a black lace mantilla and matching mask and fan” (Bess is a “southern belle” with peach gown and matching parasol and butchy George is “convincingly disguised” as a “pageboy”).

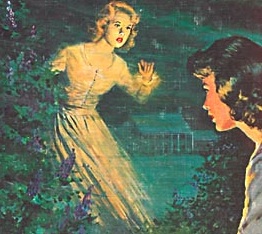

In The Mystery of the Lilac Inn, Nancy schemes to catch the ghostly figure haunting the Inn by dressing up like her in a cream colored evening dress, transparent white scarf and raven-black wig.

Some of her stuff is chimerically outdated and alluring to the modern 10 year old. Nancy often carries a “knitting bag” and matching shoes. Wait, what? What’s the hell’s a “knitting bag?! What is spider-spun silk”? The original books are a delightful melange of slangy exclamations and outdated expressions like “Hypers!” and “picklement!” Friends are of course “chums” and suspicious types are “shady characters”. Swimming suits are “swim togs”. Nancy is “vexed” rather than upset. Red hair is “titian.”

One thing you will never hear the girls say is “I’m not hungry”. That is because, second to mystery solving, eating is what these girls love best. Food is the great leveler in Nancy’s world – integral to self-care, deepening friendships, and an acknowledgment of girlish pleasure, specifically the oral delights. The gals solve mysteries and capture criminals seemingly between meals: Hearty breakfasts, delicious “luncheons”, snack stops, scrumptious dinners, desserts and compulsive cake baking. Hannah will not permit a hard day of sleuthing to commence before serving up a good breakfast of waffles – plain or strawberry -eggs and bacon; blueberry pancakes with syrup and honey and cinnamon toast. Luncheons are a young sleuth’s most important meal of the day. Hannah whips us praiseworthy “tomato cream soup, cheese souffle and peach tarts”. Or: toasted “cheese sandwiches with lots of paprika, and a cup of bouillon with a speck of nutmeg”. “The Golden Swan Tea Room” is the girl’s favorite luncheon haunt, famous for their chicken salad with homemade rolls and iced tea. Often lunch is on the run, sometimes in picnic form with “crispy fried chicken, hot corn bread, sweet potatoes and homemade pecan pie” in a basket packed by Hannah and ready in the trunk. Other times they’ll stop at a quirky roadside Inn. In The Sign of the The Twisted Candle, the chums stop for a light snack of tea and cinnamon toast, but when news comes that they will be delayed in the spooky, candlelit lobby by a storm, they quickly revise their order to “jellied consomme”, sliced breast of chicken, hearts of lettuce with Roquefort dressing, date nut bread with sweet butter, cheese and crackers and mocha layer cake”. Dinners are sit-down affairs, and time to discuss casework with Dad. Hannah serves square meals like “Steak and French fried potatoes, fresh peas, and yummy floating island for dessert”. Steaming “pots of chicken” with rice and gravy and apple pie, or spring lamb with rice, mushrooms, fresh peas and chocolate angel cake with vanilla ice cream”. Nancy rarely eats a dinner that doesn’t include soup: cream of chicken, tomato, split pea, chicken bouillon or consomme. Nancy nor her girls ever deny themselves dessert: scrumptious ice cream; floating islands; chocolate mousse; lemon or raspberry tarts; ice cream sundaes decorated with “double portions of chocolate and nuts” and zesty orange ices. Late night snacks are not out of the question either, like a hunk of pound cake with hot applesauce and a cold glass of milk. No episode of Nancy Drew would be complete if someone didn’t bake a cake.

It is a time worn tradition that teenage detectives drink a lot of hot cocoa, with dollops of whipped cream and/or marshmallows.

Eating out on location for regional eats are practically pornographic. At Famous Antoines, established in 1868, New Orleans’ finest restaurant, they feast on “Famous Oysters Rockefeller, served on the half shell on hot salt and garnished with a secret garlic sauce”. Then comes “chicken in a bag:, the waiter tore off the paper covering revealing a succulent rice stuffed bird. Dessert was pecan pie”. At Shadow Ranch, Nancy chows down on “roast beef, beans, corn fritters, apple pie, tacos, spicy chili, corn dogs with relish, potato salad and bbq beef that has been buried in a pit overnight and cooked, as the ranch hands describes, “nice an’ slow over hot stone”s. In The Hidden Window Mystery Nancy visits friends in the south whose servant, “lovable old Beulah” serves up heaping helpings of “squabs, sweet potatoes, corn pudding, piping hot biscuits, and strawberry shortcake.”

In one of the most outlandish gastronomic descriptions, Aunt Eloise really outdoes herself when she whips up a fur trapper-themed feast in her apartment, in honor of her niece’s “fur related” mystery: Nancy gets increasingly frenzied describing the feast: “She had chosen a trappers dinner. When the table was finally set with lighted candles and gleaming silver, Nancy heaved an ecstatic sigh. “Ummm….. How delicious everything looks!” Venison….and and wild rice…and… my favorite.. current jelly!!””

One chapter of a mystery actually ends with: “Tired and hungry, the campers had to face it. There was no food in the house!”/ As if that were the cliffhanger. The writer – not physically capable of leaving the kids hungry for more than half a page – opens the next chapter with a ludicrous old coot on showshoes bursting into the cabin saying “Shucks! Nobody need to go hungry! I shot some rabbits on the way!” The lunatic then whips up a delightful dinner of canned beans and freshly killed rabbit, cooked on a spit in the fireplace. Unbelievable. In The Hidden Staircase, Nancy has some sort of meal in every chapter. A tea service with dainty sandwiches, sherbet with orange and grapefruit slices, chicken salad, steak with French fries and a “lobster salad sandwich was the best thing she had ever eaten”. Bess has said: “This mystery has got me so upset that my appetite is gone.” Then she quickly changes her mind and orders a double chocolate sundae. With extra nuts.

Teen sleuths appealed to girls like me because as children, we learned pretty quickly that, it was different for boys. They had Superman, Elliot Ness and Robin Hood to pull from. Sure we had great heroines like pig-tailed free spirits Laura Ingalls and Pippi Longstocking; turn of the century tomboy Caddie Woodlawn; Ramona, Harriet, Jo March, Tiger Lilly, Scout and Anne Shirley, all independent, resourceful, and brave. But the girl sleuths took it to another level. They satisfied our desire for domination, for adventurous lives without men, for agentic feminitities characterized by our own achievement and control of our own lives. Women responded so strongly to the teen detective that Nancy single handedly spawned an entire teen detective force: Judy Bolton, The Dana Girls, Kay Tracey, Penny Parker, Beverly Gray, and a true icon in the annals of teenage sleuthery, plucky 14 year old tomboy, Trixie Belden. Trixie is the bomb. Hopelessly average, she is a slob, gets bad grades and eats like a pig. Her mode of transport isn’t a coupe but rather a spotted nag named Strawberry. Her uniform is “dungarees”. She is an excellent sleuth and a total mess and I could completely relate to her.

Trixie and Nancy and all those other teen sleuths were different. I was different. I was an under-bloomer, uninterested in boys or curling irons, not popular or pretty and I worried about it endlessly. I didn’t even know what was going on half the time let alone participate in “normal” pre-teen hi-jinx and histrionics. With Nancy and Trixie none of that mattered. They made sense to a scrawny, snaggle-toothed pre teen nerd and bookworm. I admired their character and focus, their bravery and autonomy, their spirit for adventure and the purity and simplicity of their friendships. They had their eyes on the prize. I pored over the girl’s accounts of their plotting and planning, packing for road trips, picking meals off lunch menus, choosing outfits, skulking around at night shining flashlights into alleys, climbing trees to access windows, making up secret languages, crawling along rooftops, tip toeing along creaky floorboards, snooping in people’s stuff, tapping walls for secret passages, celebrating their accomplishments over hot fudge sundaes together as girls. They never confused me. The mysteries were complicated but the girls weren’t and I was relieved that I didn’t have to figure them out or to try to glean social understanding from their lives. They were different, smarter, better. They solved crimes.

Because of Nancy – despite growing up in a mid-century faux colonial – I rummaged around in the “old” attic looking for that secret diary, the haunted doll, the stack of letters that held the secrets and clues, on an endless hunt for mystery. Oh, who am I kidding? I still do all that. My chum Beth and I spent the better part of 2 years tip toeing through the family burial plot of the 19th century house museum she managed in fear/hope that the ghost of the colonial plow boy would come to life and try to kill us (in college). It’s okay to do that stuff (I guess even if you are decades from “teenage”), if you’re playing by Nancy’s rules because specialness, character and power come from ingenuity and bravery, not popularity among peer groups. Nancy lives free of doubt and anxiety because she has all the power, she is in charge and she doesn’t lose a second’s sleep over not being like other girls, sobbing their way through overwrought personal dramas, or for being a virgin. Nancy only exists in that magical window of time in girl’s lives before they run afoul with adolescence, when everyone was still just friends. You know, before boys and school ruined our lives.

As for feminist disdain for my Nancy, I say hypers, no! She isn’t old-fashioned and will never be dated, for Nancy Drew is a complete original. She never trivializes the perks of some of the more conventional feminine stereotypes like dressing up, deep friendships and hot fudge sundaes. But after lunch she stakes out new territory by showing us how to face our fears and jump into action and go for the brass ring. She inspired girls like me not just to independence but to total domination in a man’s world. She is better than the police and better than her male counterparts, The Hardy Boys at solving mysteries, staunchly convinced of the prevailing power of womankind. As she puts it in The Clue in the Diary, “Calm your nerves. Three capable, muscular, brainy girls such as we shouldn’t need any help!”

Nancy taught us not only how to be ever vigilant for clues, but also the value of being unconventional and free from the shackles of gender expectations, by taking down every foe, subjugating every villain, dominating every man on every page then jumping in her coupe and taking her girls to lunch. She is a feminist ruled by traditional propriety, prissy but stalwart, prudent but courageous, self-centered but altruistic, self confident but modest, passionate but composed, purposeful but respectful. Nancy commands everyone’s absolute respect and has a big enough ego that she can afford to focus solely on the needs of others rather than wallow in self-absorption or in angst-fueled teenage chatter in our own head. Nancy’s opacity and lack of interior conflict may be her greatest gift. She doesn’t fool around. She steps up to the plate and points to the bleachers.

Nancy taught us not only how to be ever vigilant for clues, but also the value of being unconventional and free from the shackles of gender expectations, by taking down every foe, subjugating every villain, dominating every man on every page then jumping in her coupe and taking her girls to lunch. She is a feminist ruled by traditional propriety, prissy but stalwart, prudent but courageous, self-centered but altruistic, self confident but modest, passionate but composed, purposeful but respectful. Nancy commands everyone’s absolute respect and has a big enough ego that she can afford to focus solely on the needs of others rather than wallow in self-absorption or in angst-fueled teenage chatter in our own head. Nancy’s opacity and lack of interior conflict may be her greatest gift. She doesn’t fool around. She steps up to the plate and points to the bleachers.

Nancy is a mythic character and a girl, on the cusp of adolescence, in eternal summer, lingering on the threshold of adulthood, never passing over. She is an icon and an eternal, titan flame burning in the psyches of those of us she inspired to seek for something more than what we were told to expect. Nancy taught us to shine a flashlight on the glass ceiling and throw a brick through it. She stood up, brave and tall and valiantly answered every call to duty and we blindly followed her, down hidden staircases, through secret passages, feeling our way down dank tunnels and into terrifying places, and we emerged better because of it. She is our brave and bright hero, stepping into the dark, chasing down the shadows, facing our worst fears and conquering every one. Nancy Drew lived for us in that flash of time in girlhood when we were our best, when we were most alive and when anything was possible, and offered us a glimpse of our brave and better selves and reminded us of what a grand adventure it is, and how wonderful it is, to be a girl.