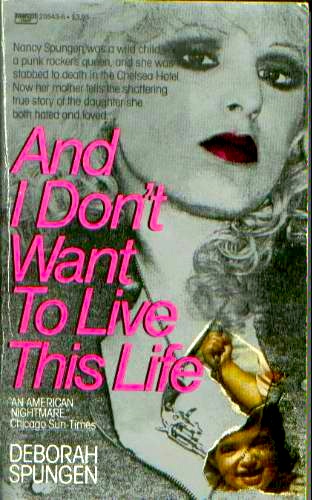

If you are expecting a collection of sordid punk rock anecdotes, put down this book and pick up the unauthorized Courtney Love biography. This punk rock The Bell Jar is an achingly sad and complex memoir by the grieving mother of Nancy Spungen, doomed sweetheart of Sex Pistol Sid Vicious. Nancy was a violent, whining, selfish, immature, cultural cipher and groupie from hell. But she was also the gifted eldest child to a middle-class, suburban Philadelphia Jewish family. And her mother loved her.

Deborah Spungen readily admits that her daughter decimated everyone and everything in her midst and that wherever she went she brought with her a double black rainbow of fear and hatred. But she also gives insight to her daughter’s damaged psyche. Nancy began her life with the umbilical cord squeezing the oxygen to her brain, jaundiced, and suffering from a rare blood disorder. Infant Nancy was impossible to console, prone to tantrums, hostile, insatiable, demanding, a bully to her siblings. As she grew older, she displayed symptoms of neurological disorders and schizophrenia. She had psychotic episodes, banging her head, attacking a babysitter with scissors and her mother with a hammer. Today we know, of course, that this child isn’t necessarily a “bad seed”. Of her defiant, difficult daughter, Deborah writes:

“It seemed as if every week she got wilder, further and further from our control and our sense of right and wrong. Our morality meant zero to her. She would simply step over the line, draw a new one, and then step over that. We were also revolted. It was ugly and distasteful and we hated to see such a bright child throw her life away—trash it, really. But we were powerless to stop her”.

In order to prevent her from ripping herself to shreds, Nancy was prescribed Phenobarbital and Atarax, which is later used to cast blame on Deborah for her daughter’s heroin addiction. Like everything in the 1970s, mental health professionals were incompetent and unenlightened, throwing their hands up. Because Nancy was bright and had moments of lucidity and warmth, she was deemed ineligible for programs equipped to handle extreme behavioral problems, and because of her behavioral problems, she was unable to function in public, private or reform schools. So, not crazy enough for “the asylum”, but not quite capable of surviving “the world”, friendless and aching for love, Nancy cast herself into the murky world of the wandering purgatory. Punk rock created a world for people like Nancy, although even in the NYC punk world of crazies, outcasts, misfits and social rejects that all banded together on the Lower East Side, Nancy quickly rocketed to the top of the list of people to dislike and avoid. Punk would be nowhere without repressive, disapproving parents, and Nancy ate it up, despite the fact that in the wild west of NYC in the 1970’s, she was an outcast among outcasts. Bullied and mocked by other groupies, called “slutty” by the other sluts, Nancy grew thick skin. When she wore out her welcome in NYC, Nancy plotted her escape to the UK to get a “real rock star boyfriend”.

Stationed in London in 1977, Nancy zeroed in on The Sex Pistols. When her first choice, adorable lead singer Johnny Rotten rebuffed her, she moved on to his less adorable bandmate, Sid Vicious. Like many 20 year old girls. Nancy just wanted to be “somebody. Just not herself. And you’ve got to handle it to her, the Times Square stripper – so reviled that Johnny Rotten described her as “screwed out of her tree, vile, worn, and shagged out” – returned to NYC with a Sex Pistol on her arm and a faux british accent.

During their vociferous, epically destructive, two year relationship, Nancy became addicted to heroin, and after the Sex Pistols broke up in 1978, she and Vicious moved to the Chelsea Hotel. In one almost touching scene, Deborah describes picking up Nancy and Sid at the Trenton train station, the pair of bruised, emaciated, punk rock junkies drawing gapes from everyone on the platform. Deborah correctly and empathetically defines Sid Vicious, not as an evil psychopath who led her daughter astray, but as a passive-aggressive, self-loathing, violent man-child. Her commentaries on the “punk” scene are astute:

“Actually, I felt kind of sorry for him (Sid). He seemed like a victim of Malcolm McLaren’s promotion machinery. For a brief time he’d been a star. Now he didn’t know who or what he was. He seemed like a genuinely confused kid…..He wasn’t so evil looking once you got used to the sight of him. ..His presence was not malevolent .It was subdued. My impression was that he simply wasn’t very bright”.

In some twisted way, Sid & Nancy’s relationship is a love story, albeit an archetypically codependent one, where the lovers regularly beat the shit out of each other. Two violent, self-loathing losers find each other and fall in “love”. Pathetic, but touching in way, too. Not so touching is the lethal wound to the abdomen Nancy suffers in room 100 of the Chelsea Hotel, later traced to Sid’s “007” hunting knife. Sid Vicious was arrested and charged with second degree murder, although the details of that day are murky and ensconced in legend. He pleaded not guilty and was released on bail. Four months after Nancy’s death, stints in prison, Bellevue, methadone clinics and rehab, he died of a heroin overdose. Sid’s own story of Love and Death, means that Nancy by association has to be magically transformed into a succubus, a vampire leading her consort to the sacrificial alter.

After Nancy’s death, Deborah’s experiences with the justice system and the media are horrific tales of indifference and insensitivity. The media was particularly brutal and outwardly cruel, gleefully referring to their dead daughter as “Nauseating Nancy”.

Thanks to the ignorance of the time, Deborah repeatedly builds to the conclusion that Nancy is beyond all help and doomed to die. The family suffered years of schools and programs and doctors and specialists assuring them that Nancy would “grow out of it”, followed by she was “too far gone”. The experts finally diagnosed her as dead before her as a schizophrenic.

From the time her daughter was a little girl, Deborah was tormented by the premonition that her daughter wouldn’t live to see adulthood. As a brutal coping mechanism, Deborah creates a “fantasy” of her daughter’s death, wherein she drifts off peacefully from a drug overdose and the family goes about their banal business. Nancy’s death, of course, was violent and agonizing and seedy. Deborah has to suffer her daughter’s legacy as a rock-and-roll footnote, a tabloid grotesque overshadowed by the death of her more famous boyfriend. It is a sad truth that in no way detracts from the fact that Nancy’s mother always loved her, no matter how hard she tried to not be loved.

A young woman is dead. I don’t care. You probably don’t care. The police don’t care. The papers don’t care. The punks for the most part don’t care. The only people that care are (I suppose) her parents and (I’m almost certain) the boy accused of murdering her.

–– Lester Bangs, on Nancy Spungen’s murder