Snow lay thick, too, upon the roof of Willoughby Chase, the great house that stood on an open eminence in the heart of the wold. But for all that, the Chase looked an inviting home – a warm and welcoming stronghold. Its rosy herringbone brick was bright and well cared for, it’s numerous turrets and battlements stood up sharp against the sky, and the crenelated balconies, corniced with snow, each held a golden square of window. The house was all alight within and the joyous hubbub of its activity contrasted with the somber sighing of the wind and the hideous howling of the wolves without.

This is how Willoughby Manor – the stately house in the creepy, moated, desolate and wolf-infested wold of Willoughby estate – is described in the children’s book, The Wolves of WIlloughby Chase. I read this book 30 years ago – and last week. It’s your classic rich girl/poor girl story. Pampered Bonnie in petticoats and her orphan cousin Sylvia in rags. Evil, evil governess Miss Slighcarp from who the brave little girls must escape. And then there are the wolves, the horrible wolves, with their sloping backs and bloody fangs, always lurking, ready to tear them all to shreds. What does any of this this have to do with Sherlock Holmes? Well nothing, but I was reading this book when I read a story about a broken down old English country house in need of saving, the picture of which seemed the spitting image of Willoughby Chase and I got the two all mixed up in my mind.

The beleaguered and endangered house is called Undershaw, and it was Arthur Conan Doyle’s home from 1896 until 1907, so it was where he wrote the creepy hound-related masterpiece The Hounds of the Baskervilles. Like The Wolves, The Hounds is your classic, gothic hound story, set in an isolated mansion in a creepy english country side. Both books have – besides the ghastly, bloodthirsty dogs from hell – inheritance plots, captives in dungeons, innocent young maids running for their lives along hound infested moors, signals by candelight, moonlight, foggy nights and sadistic lunatics.

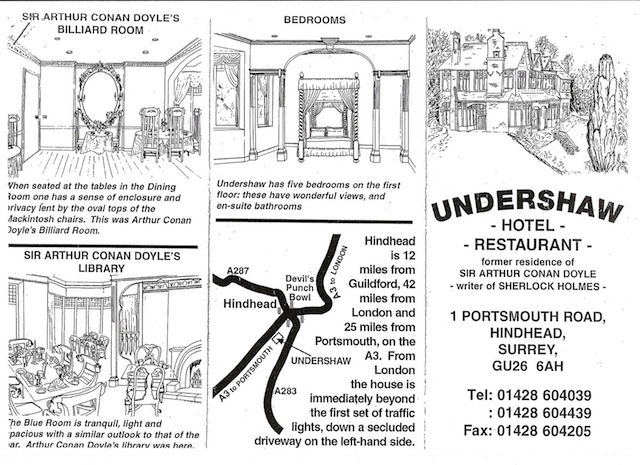

Undershaw stands in the village of Hindhead, 40 miles from London. It is an imposing rosy redbrick, late Victorian house, built in what experts like to call˜Surrey vernacular. It is set among a prospect of tall trees and waving grass, at the end of a steep drive under a hanging wood. Overlooking The Devil’s Punch Bowl, – the bowl-shaped crater that was formed when The Devil slammed his fist into the earth – and casting sweeping views down the secluded Nutcombe Valley and over the South Downs countryside, the 10,000 square foot house is set over three rambling floors, in three acres bordered by lush woods, with heavy rhododendron bushes banking on either side of the lawn.

Undershaw came about in 1892, when Arthur Conan Doyle’s wife Louise (affectionately nicknamed “Touie”), succumbed to tuberculosis and was given 6 months to live. In an effort to stay her death sentence and avoid the sedentary blanketed exile to which tuberculars were normally resigned, Conan Doyle embarked on an around-the-world hunt for a climate in which she would thrive. While checking out Switzerland in 1894, a determined and adventurous (and probably ADD afflicted) Conan Doyle became the first Britishman to cross an Alpine pass in snow shoes. Fellow novelist and fellow consumptive Grant Allen suggested that an English life might be possible for Touie in the 800ft altitude village of upland Hindhead, with it’s dry, sheltered microclimate. In the late Victorian era, the Surrey air was highly sought after, and the area in which Undershaw was built was known as “Little Switzerland”. Some of the great medical minds of the age had championed the restorative qualities of life on the Surrey-Sussex border around Hindhead and Haslemere. So in 1896, Conan Doyle paid £1,000 for a plot of land in Hindhead and another £7,000 to design and build the home. Forward thinking eccentric that he was, he equipped Undershaw with the latest gizmos and gadgets, including it’s own electricity plant and a magnificent railway on the grounds for his children. One of Conan Doyle’s many demands was extra-large windows, to provide optimum wafts of theraputic air and sun light for his Touie. Grant Allen was right about the healing properties of the Surrey air and Touie defied doctors, living for another 13 years.

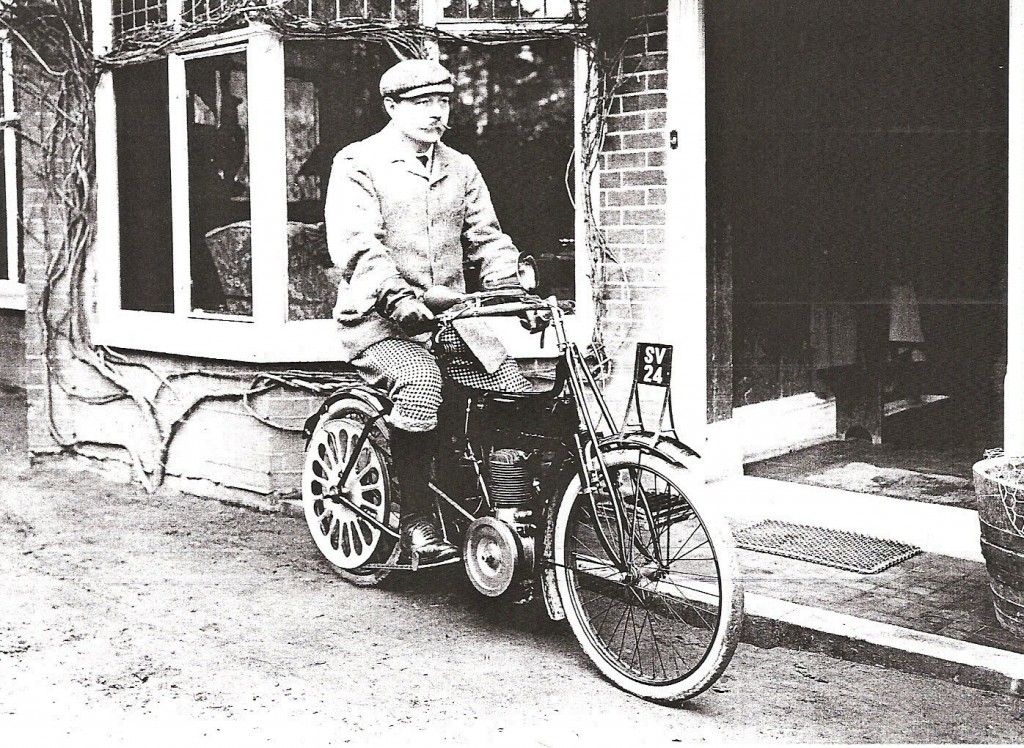

The author at Undershaw, pre wolves

This mystical spot, with it’s atmospheric and dramatic views of the South Downs countryside and it’s healing air, provided more than just a healthy environment for Touie. It also seemed to have exerted a great creative influence over the writer. In 1893, Conan Doyle had sent Holmes and Moriarty plummeting to their deaths over the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland. But less than a decade later, he resuscitated the detective in The Hound of the Baskervilles while living at Undershaw. The Hound of the Baskervilles, one of the finest crime novels ever written, explores the occult themes that Conan Doyle became fascinated with while living at Undershaw. The story’s subtle interplay between reason and the supernatural reflects the raging debate in Conan Doyle’s own mind at the time he wrote this. In the story, reason of course triumphs: the cool and calculating Holmes emerges from the shadows to orchestrate a thrilling denouement. Conan Doyle was less calculating and more open to matters of the supernatural and he devoted decades to the spiritualist movement, and was famously tricked by two mischievous little girls into believing in fairies. Undershaw specifically is said to have provided the inspiration for the thumbprint mystery, The Adventure of the Norwood Builder.

Conan Doyle described his property as an endless sea of greenery, ranges of hills piling up, one behind the other, in undulations of varying blue. An expanse which, whether seen from near or far, in unity or detail, simply ravishes the eye with its myriad beauties”.

The home was a creative inspiration for other writers as well and became a sort of hot spot for a 19th century literary brat pack that included Virginia Woolf, Sidney Paget, E.W. Hornung, J.M. Barrie, Churton Collins and Conan Doyle’s friend, Bram Stoker, who said of the home: “It is so sheltered from cold winds that the architect felt justified in having lots of windows, so that the whole place is full of light. Nevertheless, it is cosy and snug to a remarkable degree and has everywhere that sense of ‘home’ which is so delightful to occupant and stranger alike”.

The panoramic view across three counties has not changed but one would be hard pressed to see anything from that house anymore because the windows have been shattered and are all boarded up. Yes, the once majestic home, where Conan Doyle sat and wrote his greatest story, sits sorrowfully empty, dilapidated, rotting and probably haunted. Unbelievably, Undershaw has been left to rot, warp, break and crumble. It has been left to the wolves.

Thieves have stripped the lead from the roof and elks antlers from the walls. Rats have set up house. Water has been left to pour through 3 floors of the property, soaking and destroying the floors. One of the finest literary houses in Surrey and most unique in the South East for having been designed specifically for the owner, has been tossed away and is now a totally uninhabitable mess. Undershaw has been the subject of great debate since 2004, when the hotel that occupied it sine 1924 shut and their tenants abandoned the house to thieves and to the elements. An entire, civilized nation has somehow allowed this great home to become derelict, falling into an ever increasing state of disrepair, becoming increasingly uninhabitable and thus more and more difficult to argue it’s worth.

This is what neglect and abject stupidity have wrought:

Undershaw’s cozy and theatrical entrance hall at the turn of the century.

Undershaw’s cozy and theatrical entrance hall at the turn of the century.

Undershaw’s rotting and sagging entrance hall today.

Despite the deplorable state of decay, many of Conan Doyle’s personal, idiosyncratic touches remain intact in the sad house, such as it’s striking lack of symmetry and ornamental finger-plates bearing the authors monogram. Many of the demands he had made of the architect were to aid his consumptive wife and are innovative and unique, and despite the house not being an architectural marvel, it still bears an indelible imprint of his character. He had the doors designed to open on the push-pull principle, hinged both ways, to prevent unnecessary turning of handles and a quicker pass through (ADD proof), and non exhaustive low riser staircases for Touie. The “Cherry in the Snow” (the tops), is the purported secret door to the library. Even amid todays wreckage, the house is a quirky and strangely touching monument to personal and authorial vanity. In the main entrance hall, – once decorated with guns, prints, trophies and aspidistras – stands an enormous, braggartly double-height heraldic stained glass window displaying a coat of arms and the crests and names of all the grand families Percy of Northumberland, Hawkins of Devonshire from whom Conan Doyle claimed he and his wife were descended.

So how – in a country so literary-proud – could things have possibly deteriorated this far? After Conan Doyle sold Undershaw in 1907, the house fell into bad hands. For decades it was some sort of crappy theme restaurant and hotel with recycled crockery (alright it sounds pretty great). Now, after years of practically inviting vandals in with it’s titillating, Scooby-Dooesque exterior, it stands to be hacked up and made into – what else? – condos. When Undershaw was offered for sale six years ago as an ‘Investment/Development Opportunity’ it was bought for £1 million by “Fossway Limited”, a sketchy sounding Virgin Islands-based property company. Under their sinister redevelopment plan, the house would be split into “flats” and townhouses. Conan Doyle’s billiards room will become a kitchen, his stables a garage. Secret passages? Libraries or studies? Uh, yeah, no. No need for anything reading related. Master suites and faux gourmet kitchens need to be carved out. Back up the Home Depot truck and bring on the golden oak, granite, stainless steel, brass, ceiling fans, a shovel, a crowbar and a few hundred ton barrels of character-stripper, we’re comin’ to de-detectivize the house.

For some reason, it was not until 2006, with the house already in abject ruin, that The Victorian Society – the organisation responsible for the study and protection of Victorian and Edwardian architecture – spoke up, fiercely opposing plans for the property to be turned into flats and arguing that the home should be preserved for its literary history. Conservationists at the Victorian Society begged English Heritage, the Department for Culture, Media and Sports and the Government to upgrade Undershaw from a Grade III-listed building (special) to Grade II (more than special) or Grade I (most special). A Grade III listing means nothing much other than local council needs to be consulted about alterations. A higher grading would make it a matter for national concern.Amazingly, the Culture Secretary of the day, – senior Labor Party member, BBC meddler and bribe takers wife – the paraodically named villainess Tessa Jowell -refused the upgrade, arguing that the building was not of sufficient architectural or historic merit and that the writer does not occupy a “position in the nation’s consciousness”.Wait, what? Not occupy a position in the nation’s consciousness? Even people here in Los Angeles have heard of – albeit not read – Sherlock Holmes. As geniusophile Stephen Fry said about Arthur Conan Doyle: “He created one of the most recognisable and archetypal figures in literature and if his house is not worth saving, then I would say that no house is worth saving”. Poor Doyle! He dreamed of being a serious historical novelist, yet is only remembered for his pot-boilers and and now the British government has gone on record saying that no one in his homeland even knows who he is.

In it’s letter to the Victorian Society, the DCMS wrote: “The building lacks the level of special architectural interest which would justify a grade I listing. The building’s association with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, especially in view of the fact it was not the only property he occupied during his career, is not sufficient to justify a grade I listing on the basis of historical association alone.” Oh, right. Since Conan Doyle lived in that other house, too, that Baker Street House, Undershaw is not worthy of protection. Oh wait, wait that was Sherlock Holmes that lived in that Baker Street house not Arthur Conan Doyle. I keep getting those two guys mixed up! Tessa Jowell is similarly confused, Â as she was quoted as saying “The building most closely associated with [Sherlock] Holmes is 221b Baker Street. I would be only too pleased to consider listing that building Grade I should a request come forward.” Ladies and gentlemen, the “Culture” Secretary of Great Britain. The operative word being “secretary”.

Undershaw’s architect, Joseph Alfred Ball, a pupil of the great Alfred Waterhouse (Museum of Natural History in London) also designed St Agatha’s Church (“cathedral of the car parks”) in Portsmouth. St Agathas was awarded a Grade-II back in 1969 based on it’s architectural merits (the congregants successfully staved off demolition threats in 1974 and 1981). Yet the good people at English Heritage claimed Undershaw, although “interesting” does not have the architectural distinction to merit the same upgrade.  I strongly disagree, based on the architectural distinction of a secret door to a library alone but there is precedent for historical associations when architectural distinctions don’t cut it. Charles Darwin’s house (Down House) is designated  “Grade II on architectural grounds but is Grade I for historical associations“. Darwin described the boxy Georgian villa as “ugly, (it) looks neither old nor new. It’s not, of course, but it is a suburban house not Notre Dame. Down House merits attention because it is where Darwin wrote his most important work. English Heritage bought it outright now it’s a heavily renovated, fully functioning museum house with mannequins, exhibits, lunatics in period costume, room reconstructions, multimedia tours and docents coming out of it’s ears. There is a gift shop and an assortment of alarming sounding themed events like “Seafaring” and “Victorian Time Travelers Taster”.

Okay, million dollar idea that I am just giving away: Murder mystery dinners, 7 days a week, 52 weeks a year (in my calculation: $79.99 a head x 20 x 365 minus the cost of a bloddy slab of prime rib and some pudding = a lot of money). Haunted Halloween House. Holmesian story reenactments. Haunted tours on the moors (moors tours). Anyone? (Stephen Frye if you are reading this please contact me about a potential business opportunity).

The Feds have happily awarded Grade I listings to many houses on the basis of literary merit: Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, John Keats, Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Kingsley. How could anyone claim that either Gaskell or Kingsley is of more importance than Arthur Conan Doyle? Methinks there is literary snootery afoot! Is this a case of judging a book by the “seriousness” of the material? Former Arts Council chairman Sir Christopher Frayling thinks so: “If this was Jane Austen or Charles Dickens, unquestionably this house would have been preserved. Because it’s Conan Doyle and detective stories he’s treated as a second XI in literature. But he wrote some of the best-known stories in the English language.”I guess what all these preservation societies are saying is that Arthur Conan Doyle is too popular a writer to be taken seriously. If at any time in my lifetime Stephanie Meyers or Anne Rice’s houses are made into museums with gift shop, I will cry foul. Writers Julian Barnes, Ian Rankin and Stephen Fry are backing a campaign to save Undershaw from the evil developers, as are Conan Doyle’s descendants and John Gibson – an author of five books on Conan Doyle – who using his own money to fight the case to save Undershaw.

The Feds have happily awarded Grade I listings to many houses on the basis of literary merit: Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, John Keats, Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Kingsley. How could anyone claim that either Gaskell or Kingsley is of more importance than Arthur Conan Doyle? Methinks there is literary snootery afoot! Is this a case of judging a book by the “seriousness” of the material? Former Arts Council chairman Sir Christopher Frayling thinks so: “If this was Jane Austen or Charles Dickens, unquestionably this house would have been preserved. Because it’s Conan Doyle and detective stories he’s treated as a second XI in literature. But he wrote some of the best-known stories in the English language.”I guess what all these preservation societies are saying is that Arthur Conan Doyle is too popular a writer to be taken seriously. If at any time in my lifetime Stephanie Meyers or Anne Rice’s houses are made into museums with gift shop, I will cry foul. Writers Julian Barnes, Ian Rankin and Stephen Fry are backing a campaign to save Undershaw from the evil developers, as are Conan Doyle’s descendants and John Gibson – an author of five books on Conan Doyle – who using his own money to fight the case to save Undershaw.

Alarmingly, the picturesque town of Surrey has twenty one sites on the English Heritage’s “at risk” list. If you want to be really depressed, check out these and pause at “Lord Rosebery’s Riding School”.

The awesomely wacky author tooling around Surrey on some sort of…….motorized bicycle?

Famous dead writers are often looked after by a literary society or “carer”; a very few have two carers; Doyle has three societies devoted to his memory. That is because he was more than just a writer of detective stories. The great, popular writers of his time, such as Kipling, G K Chesterton and H G Wells were not just writers, but figures of social influence; wise sages and oracles to whom their legions of readers instinctively turned. No one was more universally venerated than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The nutty Scotsman with the walrus moustache was revered. Unlike any writer I can think of today, Conan Doyle was an actually talented, prolific and brilliant person who touted a wide variety of talents and accomplishments. He was a licensed surgeon, a talented sportsman, a historian, star lecturer, foreign correspondent and an accomplished adventurer. He took a mobile hospital to the Boer war, wrote plays for Sir Henry Irving, imagined the first bulletproof vest, stood twice (unsuccessfully) for parliament, played cricket for the MCC, was knighted and appointed Deputy-Lieutenant of Surrey. He campaigned for the reform of the Congo free State, penning The Crime of the Congo.

Sherlock Holmes’ purpose in life is declared in his debut in A Study in Scarlet and would also come to dictate much of Conan Doyle’s subsequent career – not always to his liking: “There’s the scarlet thread of murder running through the colorless skein of life, and our duty is to unravel it.” Conan Doyle was a champion of causes and an amateur detective in his own right and tried unsuccessfully to save his friend Roger Casement from the death penalty when he was convicted of treason during the Easter Rising, arguing that he had been driven mad and was not responsible for his actions. He successfully cracked two big cases, defending a couple of colorful characters and employing the same empirical reasoning as his character to expose the truth and In 1907 he exonerated a shy, young Parsee lawyer named George Eldaji who had been railroaded by racist officials and convicted of mutilating farm animals. Conan Doyle studied the facts which revealed that because of the young man’s astigmatic myopia, it would have been impossible for him to have attacked cattle and horses in the dead of night as alleged! (the story of Conan Doyle and Edalji was fictionalized in Julian Barnes’s 2005 wonderful novel, Arthur & George). On another case, he sleuthed on behalf of Oscar Slater, a Jewish gambling-den manager who was railroaded in the gruesome murder an old Glasgow woman in 1908. Slater slipped a note to an about-to-be-released fellow convict instructing him to “get in touch with Conan Doyle”, which the recipient smuggled out under his dentures. Slater was exonerated of the murder. “Sir Conan Doyle,” the freed man wrote to his champion as if at the thrilling conclusion of a Holmes story, “You breaker of my shackles, you lover of truth for justice sake, I thank you from the bottom of my heart for the goodness you have shown towards me.” The gaps in the legal system exposed by Conan Doyle led directly to the institution of the Court of Criminal Appeal.

Awesomely, Conan Doyle was said to have spoken with the same highly charged dialogue he wrote for Sherlock Holmes. P G Wodehouse recalled Conan Doyle talking about some school’s unauthorized use of his name. “What most people at this point would have said would have been ‘Hullo, this looks fishy,'” Wodehouse wrote. “The way [Conan Doyle] put it when telling the story was, ‘I said to myself, Ha! There is villainy afoot!'”

Even if “England” doesn’t respect Conan Doyle as an “author” then perhaps they could recognize him as the national treasure that he is. Sure, has won worldwide immortality as creator of “the world’s most famous man who never was”, in Orson Welles’s words. Sure, the character of Sherlock Holmes singlehandedly defined the archetype of the brilliant but troubled detective and laid the brickwork for what we still expect of all our great fictional detectives: That they accept their “duty” to do good – but also be personally flawed. Sure, he put deerstalking hats on the map and made illicit drugs not only seem cool but a necessary evil to a brilliant, crime-solving mind. But the Sherlock Holmes oeuvre represents only a fraction of Conan Doyle’s voluminous canon. He was psychotically prolific, and wrote scores and piles of books, biographies, historical tomes and novels, essays and stories. He created serialized heroes apart from Sherlock Holmes like the swaggering Napoleonic cavalryman Brigadier Gerard and giant headed, homicidal meglomaniac Professor Challenger, who discovered a lost world of dinosaurs a decade ahead of Steven Spielberg. And his status of inventor of the most famous amateur detective in literary history speaks nothing to his richly varied, insanely productive, brilliantly accomplished, larger-than-life…. life. After all, the epitaph on his gravestone does not read “Creator of Sherlock Holmes”. It reads:

STEEL TRUE

BLADE STRAIGHT

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

KNIGHT

PATRIOT, PHYSICIAN & MAN OF LETTERS

It is appalling when you consider the millions of tourists that flock to Baker Street – the majority of whom, like Tessa Jowell, think that they are visiting Sherlock Holme’s actual house – exiting through the gift shop, dragging sacks of tchotchkes, postertubes under their arms, while the author’s actual home sits a few tube stops away. That fake house receives more visitors than both Jane Austen’s house, Rudyard Kipling’s house and the Dickens’ House Museum, which are all Grade I-listed. Just last year, I myself made a beeline to 221 Baker Street (even the address only existed in Conan Doyles mind. In the Victorian era, Baker Street went up to only number 85. Yet there it is). I greeted the fake London bobby patrolling the front, paid my £6, photographed myself in various Sherlockian scenarios with or without deerstalker hat and meerschaum pipe, snooped and surveyed the shoddy displays with their perfunctory attention to Holmesian detail (no bearskin rug!), flopped into and out of anachronistic, flea market chairs and sofas, and finally, rang up my sacks of dry goods at the gift shop. As an avid enthusiast I felt the need to be near the creation of something, even if it was fake and tawdry. So if Conan Doyle did  nothing else of merit in his whole life, he certainly brought a lot of tourists, like myself, to that gift shop.

Steven Fry is quoted as saying: At this time now, Undershaw is to be re-titled Underthreat. As an admirer of Doyle and his achievements, I urge Waverley Borough Council to reconsider what future ages will adjudge [to be] a foolish, short-sighted and wanton act of vandalism.”

Ruddy condo-lover Adam Taylor-Smith of Waverley Borough Council retorts: “We are in financially difficult times and there is no available public money for this nice-to-have project.”

Goodbye, Undershaw. It was “nice-to-have-you”.