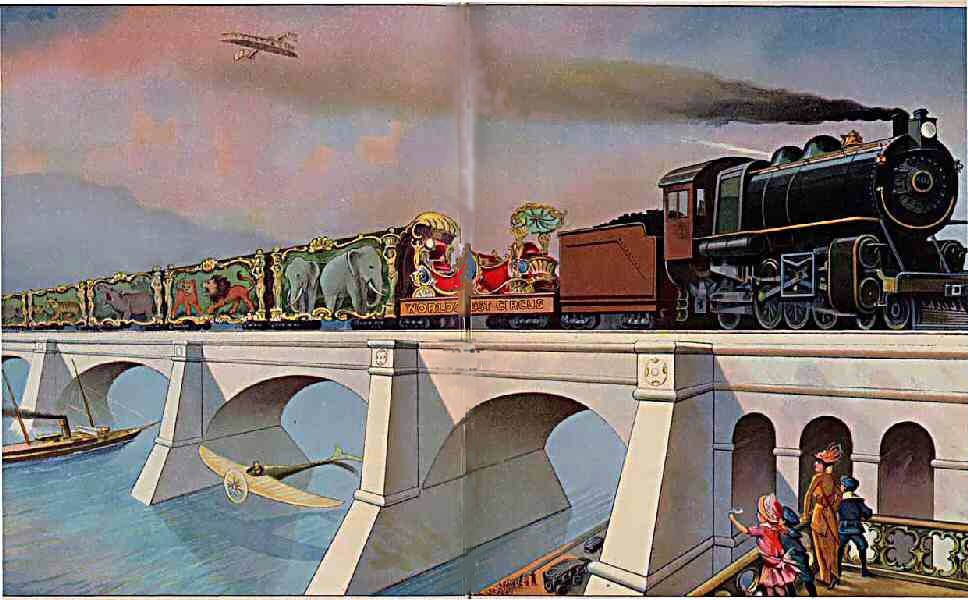

On the morning of May 30, 1893, the circus came to town unexpectedly in Tyrone, Pennsylvania.

A circus train convoy chock full of circus animals fatefully rounded a bend of a rural Pennsylvania mountain. The train was approaching a bend that was notorious for crashes. While 17-car coal trains could negotiate the steep mountainside with just one locomotive, many of the 17 cars on the Walter L. Main circus train were twice as long as the average coal car. The engineers wired ahead to request more braking power but were denied. As they guided the train down the slope, it quickly picked up speed and couldn’t be stopped. The locomotive at the front made it around the curve, but the cars behind it flew off the tracks near a farm owned by a man named Hiram Friday.

The conductor was going 40 miles an hour when the circus flew off the rails and careened down a 30-foot-high (10 meters) embankment, fourteen of its 17 carsgold-gilt, steel-barred wagons crashing one on top of the other. Fortunately,, the performer car had stuck to its track. But even so, five circus employees were killed. The animals, mostly at the front of the train, bore the brunt of the suffering. Two “sacred cows” and at least 50 horses died in the wreck,. The Walter I. Main circus was known for its horse acts, such as chariot races and juggling shows performed on the animals’ backs.

Countless animals were injured. Those who weren’t seized their chance at freedom. Hundreds of animals – tigers including a rare bengal tiger, lions, zebras, camels, horses, crocodiles, pythons and a gorilla known as the “Man-Slayer” – took the opportunity to slip their broken chains and cages and streamed out and scurried off into the surrounding forest.

.

The elephants survived, albeit with some injuries, and the sturdy beasts were even put to work in the accident cleanup.

No one knows where the circus animals that died in an 1893 train derailment are buried—or where the ones that survived escaped to. While the lore would linger for decades, the wreckage from the accident was cleared in just three days. Amid the swift cleanup, the dead animals were buried in trenches on the Friday farm along with other wreckage too mangled to be reused. But there is no documentation of the mass grave’s exact location. Some animals survived the crash only to be killed after they bolted from their broken cages. In the most famous incident, Hiram Friday’s daughter Hannah was milking a cow a few days after the wreck when a Bengal tiger attacked and killed the cow. A bear hunter had to be called in to find the tiger in the nearby woods and shoot it. The beast’s skull hangs in a local hunting club today.

Still more escapees may have evaded capture altogether. In the months and years after the accident, the local papers were peppered with reports of exotic animal sightings. Townsfolk on their way to church one Sunday morning reportedly saw kangaroos hopping across the street. Men out fishing saw strange birds, likely parrots, that made the treetops look as if they were dabbed with colorful paint. A year after the accident, on Ascension Thursday (celebrated by Christians as the day Jesus ascended into heaven), revelers at a barn-raising at the Friday farm reportedly left before dark out of fear the circus animals were still lurking on the property.

Today, the story has become ingrained in town lore. Big snakes are eyed with suspicion as possible descendants of escaped crash survivors.Bones, horseshoes, lion-cage locks and railroad spikes have turned up every time a new home is built on the site. But the exact location of the mass grave of dead circus animals has been lost to history.

Long after the circus’ departure, the century-old tragedy has haunted Tyrone. The escaped animals persisted in local lore. For years, townsfolk would report kangaroo, parrot, and snake sightings, presumed to be the descendants of those freed performers.

Between 1895 and 1958, the town of Tyrone honored its dead with a memorial service for victims both human and animal.

In 2009, a memorial service was held for the human and animals victims of the Walter L. Main Circus Train Wreck. Lulu and Chang, a pair of Asian elephants from the visiting Hanneford Circus, were the first elephants since 1958 to lay a wreath in honor of the crash victims.

The Rev. Norman Huff, who conducted the brief memorial service, said the animals are God’s creation, and despite controversy that dogs modern circuses about the treatment of animals, they are well cared for and loved.

Following the service, the first elephant luncheon in Central Pennsylvania was conducted and Lulu and Chang devoured mass quantities of apples, hay and carrots.

The placing of a wreath by an elephant is one of the greatest honors as a memoriam for anyone connected to the circus.

The circus was stranded in Tyrone for a week in 1893, while the train cars were being fixed at the nearby railroad shop in Altoona, then it pressed on. Despite the horrible accident, the show did, in fact, go on.

This brings me to one of my favorite Onion pieces ever: Train Wreck Not Funny, Investigators Emphasize