This is too much, I almost can’t take it. I am a sucker for urban archeology, it makes me faint with joy. There’s something chillingly fascinating about an abandoned building and the way it acts as a time capsule for life ways past, or a sit, shuttered and stopped in its tracks in time. I once almost jumped out of a moving car upon seeing a sign that read “Santa’s Village” covered with overgrowth on the side of the road near Arrowhead, CA. I dragged my companion out of the car and into the brush to discover a children’s theme ark, still standing. Truly “pristine” abandoned spaces are rare. Consider the Notting Hill tube station decorated with 1959 movie posters, a 1932 British home, and a New York City tram stop.

An undisturbed apartment in Paris an example of perhaps the most compelling of all abandoned sites: the “time capsule” left as it “really was” in an un-staged moment arresting the flow of a distant material life.

Sometime during World War II, a Parisian woman named Madame de Florian, with the Nazi’s merely a few kilometers away, fled to the south of France, leaving everything she owned behind. She locked up her apartment on the Right Bank near the Opéra Garnier and left. She never returned.

No one knows why Madame de Florian never returned to her beloved Parisian home, but she continued to pay the rent right up until she passed away aged 91 in 2010.

Yes, since 1942, the apartment has been sitting untouched, uninhabited, under lock and key, a sleeping beauty, with no hint of what was inside. On a wintery December afternoon in 2010, a Commissaire Priseur (Auctioneer), named Olivier Choppin-Janvry, turned the key of the apartment for the first time in over 70 years. The decadently glorious apartment remained frozen in time, a time capsule recording the precise moment of de Florian’s sudden flight.

Behind the door was a perfectly preserved treasure trove of turn-of-the-century objets, an untouched piece of its history nestled deep within today’s bustling and brightly lit city streets in Paris’ 9th arrondissement.

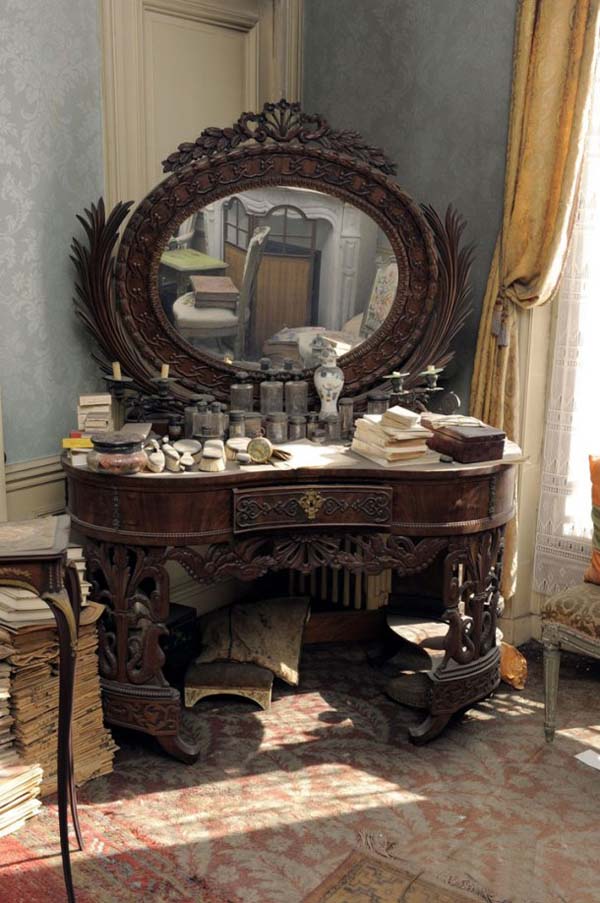

Through layers of dust and cobwebs lies a Belle Époque interior, harkening back to the feminine elegance of 18th-century France, but with eclectic 19th- and 20th-century touches, like Persian rugs, oil paintings, mirrors and toys. The walls, covered with peeling damask and pink floral wallpaper, are quietly luxe backdrops for painted Louis XV- and Louis XVI-style in the drawing room and parlor.

Under a thick layer of almost protecting dust, treasures and life waited patiently for Madam’s return. The beauty products and combs and brushes magnify the evocative human absences of the space, summoning hints of everyday life, a specific personality, a lost historical moment. The apartment is an ideal ruin because it evokes human presences: where she sat to read her letters and to apply her makeup, those things that appear dropped in place and left in the wake of a breathing person. There is a notion of “disturbance”, that we are intruding into what was possibly Madam de Florian’s most personal and vulnerable moment. Human interventions are as predictable dimension of decline as rain, but resist “staging” ruins. In that sense, the apartment left untouched for 70 years is an un-orchestrated material space unlocking a particular moment and place, evoking feelings of something that is not quite a memory, an effect magnified by the papers, combs and perfume bottles, the most commonplace of material things, their historical distance underscored by dust and the patina of past habits and styles.

There are aristocratic trappings of a different era, including quite a few wizened taxidermy pieces (a sign of affluence, not white trashery), and mountains of ephemera ranging from dressing tables to Disney toys. Notice the etched decoration in the glass window behind the ostrich — an authentic Belle Époque detail.

I don’t think my sister could even invent this tableau: a taxidermy ostrich in a damask drape next to Mickey Mouse, in front of a door with etched Belle Epoque designs on the glass.

I don’t think my sister could even invent this tableau: a taxidermy ostrich in a damask drape next to Mickey Mouse, in front of a door with etched Belle Epoque designs on the glass.

The unpainted Renaissance- or Louis XIII-style in the dining room is similarly stocked with a rich host of Belle Époque domestic material goods: luxurious furnishings and curiosities, works of art, antique toys, evidence of a past life. It’s also a reminder of how much 19th century was still alive and well at the mid-20th century. It gives a glimpse of the world that was swept away during World War II and was subsequently replaced by suburbs, shops, credit cards and iPhones. The apartment was already a bit of a stylistic anomaly at the outset of World War II, and the life of de Florian and her descendants is not at all an example of everyday Parisian life. The fascinating thing about the apartment has less to do with wealth or style, rather it is most compelling as 40 square meters frozen in their place, an arrested moment into which we can now step.

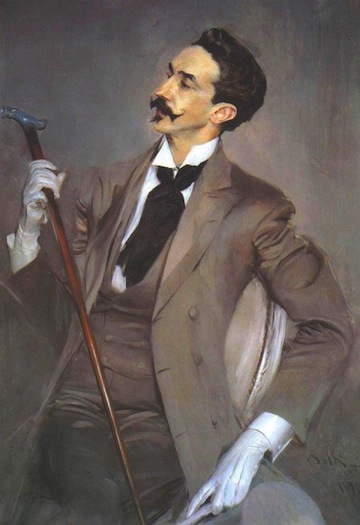

Thern there is the mystery. And it is straight out of Nancy Drew. In the apartment hung a magnificent painting of a beautiful raven-haired woman in a sumptous and revealing rose muslin dress. The woman in the painting was Mrs. de Florian’s grandmother Marthe de Florian, a socialite of the Belle Époque. Born Matilda Baugiron in 1875, Marthe was an actress, courtesan, a demi-mondaine. To be a demimondaine, or upscale courtesan of her day was a somewhat respectable life in the 1800s despite what we imagine their prudish victorian ways to have been. She was a fun-loving lady, her apartment situated near the Pigalle red light district and Opera.

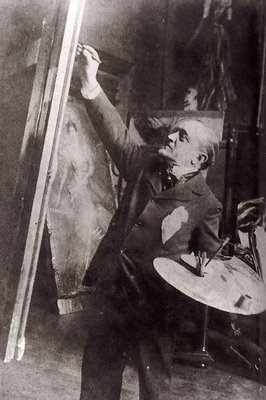

The style of the painting seemed familiar to one of the inventory team members, who suspected it might be something important, but could not find any record of the painting. He suspected it was painted by Giovanni Boldini, a fashionable portraitist and one of Paris’ most important painters of the Belle Époque, but it was not listed anywhere in the catalogue of the artist.

Also in the apartment were stacks of love letters, tied with blue ribbon. The love notes were from a host of suitors including Prime Minister and future “Tiger” Georges Clemenceau. Marthe de Florian was famed for her captivating beauty, ever surrounded by swirling rumors that she was lover to numerous great men. Amongst the love letters was a scribbled love note quickly recognized as a calling card from Giovanni Boldini.

Only after an extensive search, was a reference found in a book published in 1951 by the widow of the artist, saying it had been painted in 1898 when Marthe was 24 years old. Boldini gave the painting to Marthe as a gift. Boldini, who apparently had quite an appetite for beautiful ladies, was well-known for his flattering portraits of rich, famous and royal women in sumptuous gowns.

(left, is Boldini, right a self-portrait, lol).

After the discovery of the Marthe de Florian painting, naturally, the art world went nuts for the whole story and it sold at auction for €2.1 million ($3 million).

A place left untouched and undisturbed since one of the darkest time of Paris is haunting, chilling and moving My only regret is that I can’t cover it all with Mod Podge, preserving it as is forever. It is chilling to think of the things left behind, frozen in time. Chronal confusion over a story like this reveals how compelling pockets of the past are worth a lot of money to those who can repossess them in post-Postmodern culture, euphemistically known as cultural references. Historical artistic bits and pieces are reinvented historically into our jumbled reality of copyrights, until the past is one big subterranean garbage dump, ripe for plunder. The Paris Apartment blog noticed that Madame de Florian captured the attention of Gwyneth Paltrow, who paid tribute to the Paris apartment story with a fashion shoot , the cachet acquired, the historical weight oddly stripped away in the Millennial entertainment afterlife. What are you looking at, the original or Gwyneth Paltrow? Do you know? Does it matter?

Beyond being a rare confluence of abandonment and preservation, this kind of “time capsule” site is a somewhat ambiguous notion of ruins. Ruination is an active process to which all materiality is subject, and in fact the patina of the 70 year old dust and the cobwebs covering the Paris apartment provide it some of its symbolic power. We hope to arrest that natural decay process in our own homes, but the truth is that my writing room is lapsing into ruin this very second.

The Paris apartment has remained in the hands of the Florian estate, holding the mysteries of both Marthe and Madame de Florian firmly behind ornate closed doors.